An unprecedented Match year left hundreds of U.S. medical students with no residency destination, a trend experts say will increase in future years. But MCV Campus students proved to be strong contenders, especially in highly competitive programs.

Chris Woleben’s tool kit is one reason why.

Match Day is supposed to be the culmination of four years of medical school, an exciting day of tearing open the envelope and learning your destiny.

For some students, though, that envelope doesn’t come.

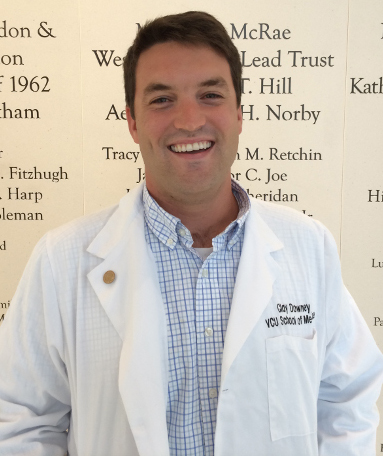

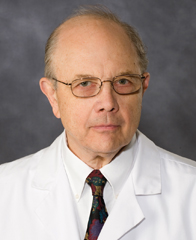

That doesn’t mean they’re not qualified to practice medicine or even that they’re below-average students, says Christopher Woleben, M’97, H’01, who is associate dean for student affairs at VCU’s School of Medicine.

It could mean that their strategy for the Match wasn’t adequate – or unfortunately, there are just not enough residency slots available in the system.

Christopher Woleben, M’97, H’01

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

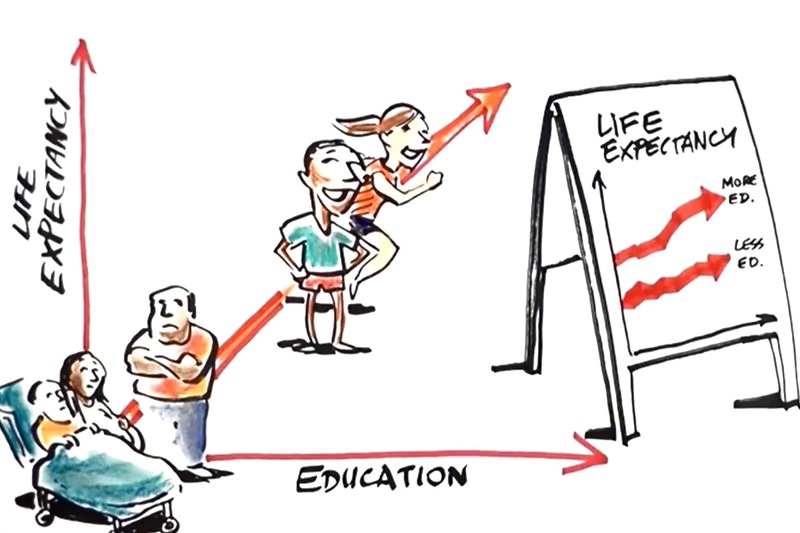

By the year 2020, the United States will face a shortage of more than 91,500 physicians, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). By 2025, that number is expected to grow to more than 130,600. It’s a shortfall that’s equally distributed among primary care and specialists.

At first, the solution seems obvious: increase the number of students in medical school. And so VCU and other schools have increased class sizes (the incoming class on the MCV Campus is 216 strong, with plans to increase to around 250) and new programs have sprung up around the country.

But there’s a catch. To complete training, of course, physicians must complete a residency program.

Unfortunately for today’s students, the number of federally funded residency training positions was capped by Congress in 1997 by the Balanced Budget Act.

“The concern is that as medical class sizes increase, as more schools come on line and as more international medical students apply for positions in the United States, the number of open residency first-year positions is remaining stagnant, and the Match process is becoming more and more competitive,” says Woleben.

It’s a basic economic conundrum: demand exceeds supply, and so some students won’t get an envelope. That affects not only the student’s future, but the future of medicine in the U.S.

John F. Duval is chief executive officer of MCV Hospitals and chair elect of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s board of directors. He has a keen interest in ensuring an adequate workforce for the coming physician shortage, and the VCU Medical Center, like many other institutions, funds some residency positions without federal support. But it’s not enough. “There has been some growth, because individual institutions have elected to try and address local needs,” he says. “However, growth is not proportionate to the expansion in the number of medical graduates, be they allopathic or osteopathic.

“And so you have a train wreck in slow motion because you have the rate of growth for residency positions that is lower than the growth rate of new graduates.”

So what can be done? Budgets are tight everywhere. The AAMC and other organizations have lobbied legislators to fund more residency positions, an attempt that has not yet been embraced by Congress.

HEADING OFF THE HYSTERIA

In the meantime, universities have tried to make their graduates as competitive as possible.

VCU’s School of Medicine typically equals or exceeds the national average of 92-94 percent of students matching, and the school is nationally recognized for measures it takes proactively to ensure stronger matches.

Several years ago, Woleben developed a “toolkit” – a series of student surveys to identify and troubleshoot potential issues students may face in the residency application process. The AAMC recognized its value and published and shared the toolkit with its members nationwide. Since then, other institutions have looked to Woleben for guidance on dealing with potential Match problems.

The toolkit is used during the fourth year of medical school, as students are preparing their rank lists and seeking interviews. It helps spot students who are not receiving as many interview offers as other students. With that knowledge, advisors can intervene to encourage students to apply to more programs or change tactics early enough to be effective.

LOOMING PROBLEM?

In 2013, 26,504 students started medical school in the U.S. In a few years, they’ll be competing against more than 14,000 international graduates and graduates from previous years for fewer than 27,000 residency positions.

In fact, Woleben hones in on students’ aspirations well before that.

“I think we do focus a little more individual attention on our students than other schools,” says Woleben. “We’ve developed a four-year comprehensive career advising program so that each year, students are getting key pieces of information that will help them in the Match. We’ve strategically designed our curriculum to be longitudinal. We take time to meet with each student, to develop an individualized plan and track their progress.”

Obviously these are bright students – they got into medical school – but some face unforeseen challenges with family, health or other issues.

“We look at the total academic progress of the student,” says Woleben. “We want to make sure we’re graduating students who meet the competencies that are required to be effective, safe healthcare providers. At Promotions Committee meetings, that’s where we focus our discussion regarding individual students who are struggling. Is this student going to be an effective care provider? That question often goes hand-in-hand with whether they’re going to match into a residency program.”

VCU offers myriad resources to students, says Woleben, including help with study skills, time management, test taking and determining disabilities that may require accommodations. Deans and advisors regularly discuss student progress and work to create individual plans for students.

MAKING A PARALLEL PLAN

So if the surveys and administrators identify a student who might be at risk of not matching, what can they do? Advisors are asked to provide realistic expectations, encourage applications to “safety” schools and guide students to consider a residency that might not be as competitive but will still align with their career goals. Students need to have a parallel plan to increase chances of matching.

“When students are selecting programs for their application, I encourage them to have a balance between ‘reach’ and ‘safety’ programs,” says Woleben. “Often, our students find that they end up matching into their reach programs.”

For some specialties such as pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, neurology, physical medicine and rehabilitative medicine, students may safely apply to 15 to 20 programs, he says. For residencies that attract a higher number of applicants – surgical subspecialties such as urology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, dermatology or plastic surgery – looking at 60-plus programs with a goal of getting 10 to 15 interviews is often recommended.

Even with that strategic planning, sometimes the worst can happen.

“In 2014, we had 14 students go unmatched, a little bit higher than usual,” says Woleben. “We saw a similar trend that other schools saw: students applying to more competitive programs were going unmatched in higher numbers.

“We all did a good job of advising weaker students to make revisions to their plans, but we saw some of our stronger students were not as successful as in the past.”

“I don’t sleep well for a week before the Match, and I don’t think the students do either,” says Woleben.

By noon on Monday of Match Week in March, students learn if they’ve matched or not (though they don’t find out where they’re headed until Friday, when the envelopes are distributed around the country).

So what happens to those who don’t have a match?

SOAP OPERA

Since 2012, the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) has run the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP) for students who come up empty-handed on the Monday of Match Week. Those students submit applications to programs with unfilled slots. For many, it’s a second chance to get

the coveted envelope on the Friday of Match Week.

It’s a very emotional time, says Woleben.

MCV Campus administrators, program directors, career counselors and personnel from University Counseling Services are on high-alert starting at noon Monday to meet with students who might need to consider other specialties.

“By 2 p.m., they have to start applying to open programs, and sometimes that requires they apply to

a specialty they haven’t applied to before. It’s really fast-paced, and there is a lot of emotion in those two hours. We try to supply as much support as we can,” says Woleben.

Over the course of Match Week, applicants who did not match or only matched to an intern year may endure multiple supplemental rounds. Applicants can receive multiple offers during each round and must decide quickly since these offers are valid only for a two-hour period.

Adam Carter, M’13, was shocked on the Monday of Match Week to learn that he only matched for his intern year and not into a full dermatology residency. “Everyone had told me I had nothing to worry about,” he said. “It seemed so simple before Match Day: you go to med school, apply for a residency in dermatology, get it and go. And then Monday hit, and suddenly everything was very complicated.”

He knew he was applying for a competitive specialty and would have a better shot at something less competitive. “It made me step back and think about whether this was something I really wanted to do. And through not matching, I realized that this was absolutely what I wanted to do and nothing else in medicine would make me as happy as dermatology.”

While Carter completed his intern year, he reapplied for dermatology and accepted a dermatology position he acquired outside the Match and SOAP processes. In doing this, he was able to begin his residency this year and is currently a dermatology resident at New York Medical College. He volunteers to talk with fourth-year students who find themselves in the situation he faced last year.

“One of the things I learned from people I met ‘on the trail’ this year was that these applicants are very, very bright individuals,” he said. “But the numbers just aren’t working out for everyone.”

In 2014, by the end of Match Week, only five VCU students remained unmatched. Across the nation, several hundred U.S. seniors still did not have a residency position. Some opted to take a “bridge” year – perhaps earning a master’s degree or doing research – and come up with a new strategy to get a residency position the next year.

Administrators at VCU and other schools ponder whether it’s fair to let students continue on if they’re not good candidates for Match, perhaps racking up more debt. It’s an ethical dilemma, says Duval, without a clear solution. Another topic of discussion at American institutions is whether or not U.S.-trained students should have priority over foreign students, helping the Match numbers, perhaps, but taking away valuable diversity.

For now, the problem is only going to get worse as medical schools graduate more and more students who need residency positions. The AAMC has urged lawmakers to lift the cap on the number of federally supported residency training positions and increase funding soon to avert the looming crisis of physicians.

Lawmakers have responded with proposals in the House and Senate to increase the number of residency positions, but those bills have languished in committee.

What can today’s physicians do? The AAMC encourages them to contact lawmakers to explain the problem and make the case for taking action.

“There is not a front-of-mind awareness that this train wreck is occurring,” says Duval. “I do believe that we need to take the opportunity and start educating the broader medical community about forward-looking issues within the workforce.

“That is a right, reasonable thing for us to do.”

This article by Lisa Crutchfield first appeared in the fall 2014 issue of 12th & Marshall.

October 21, 2014

He hopes to release specific findings and guidelines in the next few months. Already, he has helped develop a Concussion Coach app that supports self-management of symptoms for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

He hopes to release specific findings and guidelines in the next few months. Already, he has helped develop a Concussion Coach app that supports self-management of symptoms for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.