This story was published in the fall 2021 issue of 12th & Marshall. You can find the current and past issues online.

Appointed chair of the School of Medicine’s Department of Emergency Medicine just four months into the coronavirus pandemic last year, Harinder Dhindsa, M.D., faced a health care crisis that was also an unprecedented leadership challenge.

On faculty for 25 years, Dhindsa served as interim department chair before stepping into his new position, where he leads more than 70 faculty members and oversees VCU Medical Center’s busy emergency department. Accustomed to caring for the range of conditions and complaints that bring people to the region’s highest volume and acuity ER every day, the department – like hospitals nationwide – suddenly confronted the realities of a pandemic in which each of those patients also might carry a highly contagious and potentially deadly virus.

“My biggest concern from day one,” he says, “was to protect our team so that we could continue to care for our patients and our community.”

Though COVID-19 was a new threat, Dhindsa’s commitment to his people and his patients was long-established, says Kathy Baker, Ph.D., associate vice president of nursing and associate chief nurse for VCU Medical Center, who has worked with Dhindsa for a decade.

“He is a boots-on-the-ground leader,” says Baker, who earned her master’s and doctoral degrees from the VCU School of Nursing. “If there is a problem to be solved, he is ready to roll his sleeves up.”

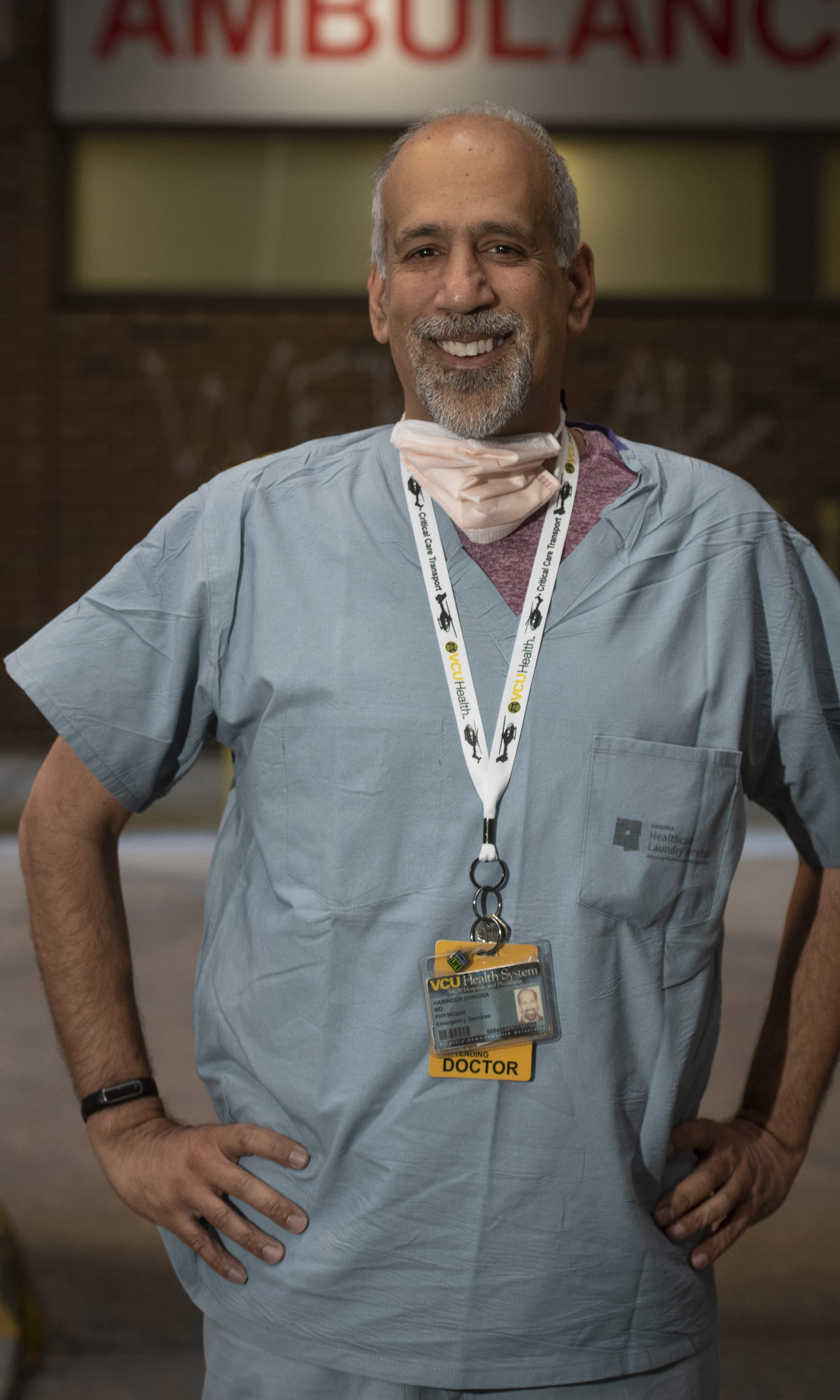

Harinder Dhindsa, M.D. Photography by Allen Jones, VCU University Relations

‘All hands on deck’

To get the job done, Dhindsa cultivates cohesive work from a broad-based team. From faculty, residents and nurses to technicians and environmental services, he says, “Emergency medicine is a completely team-based discipline. It is all hands on deck.” He cites in particular the united leadership and collaborative relationship between physicians and nurses.

As for his own role, he believes that effective leadership is “surrounding yourself with people who are really good at what they do and then standing back and empowering them to do their jobs.”

Baker agrees. Calling Dhindsa a “champion of good ideas,” she says, “We share a common goal of making sure our patients are taken care of, but we do this by supporting our teams.”

So, Dhindsa says, when it became clear that the coronavirus was going to be “a crisis of proportions we had never seen,” protecting his team and preserving the department’s ability to care for patients became the top priorities. “We organized an incident management team of physicians, nurses, and other personnel,” he says, “and we divided up responsibility to determine all the modifications we had to make to safely and effectively deliver care.”

There was the ever-present threat of the virus itself; even patients presenting without typical COVID symptoms were regularly testing positive. To increase safety for staff and patients alike, the department initiated innovations including a rapid triage system to isolate likely COVID patients; remote at-home oxygen and vital-sign monitoring and telehealth visits that allowed less-seriously ill COVID patients to safely remain at home; and a Virtual Urgent Care program, by telephone or computer, to assess and treat patients with less serious, non-COVID complaints who might not need to be seen in person.

But along with seeing to medical needs, staff members bore the emotional weight of having to step in for family members who could not be present due to visitor restrictions — sometimes in the final moments of a patient’s life. “They made sure that nobody died alone,” Dhindsa says. “But it is enormously stressful when you are FaceTiming a family member, and that may be their very last communication with their loved one.”

Dhindsa is deeply proud of the work his team put in throughout the worst days of the crisis. “They put their fears aside and came back every day for their colleagues and patients,” he says. “Their ability to adapt to a crisis situation day after day, and to come up with solutions, a lot of times on the fly, to resolve problems and issues — when you see that as a leader, it makes me want to work that much harder to support them.”

Baker says that support from Dhindsa was evident. “He was in the trenches caring for patients. He was here on nights and weekends making sure our teams had what they needed.”

Innovations expand care beyond the walls of the emergency department

VCU Medical Center emergency department serves an average of more than 100,000 adult and pediatric patients annually.

LifeEvac flights average 1,200 annually and crews are trained to provide critical care en route to the facilities.

Virtual Urgent Care program launched in May 2020 and has served more than 4,850 patients.

Remote in-home monitoring allowed 838 COVID-positive patients to recover safely at home.

ProPER (Providing Post-ER) Care Clinic launched in October and has served more than 1,000 patients with complex health needs, reducing ED readmissions.

‘Ready for everything and anything’

Dhindsa’s interest in emergency medicine began when he was certified as an emergency medical technician while a University of Maryland undergraduate. Throughout medical school – also at Maryland – he volunteered as an EMT with the Montgomery County Fire and Rescue Service, and he found himself drawn to the challenge of having always to be prepared for the unknown.

“Working as an EMT, you never know what you have until you arrive on the scene,” Dhindsa says. “There are a lot of parallels with emergency medicine because you never know what is going to come through the doors of the ER, and you have to be ready for everything and anything.”

An emergency medicine rotation as he began his fourth year of medical school cemented his commitment to the specialty. “I met some really fantastic role models and specialists,” Dhindsa says. “I looked at their humility, and their skill set, and their team-based and organization-based focus, and I thought, ‘These are the people I want to be like.’”

His interest in EMS continued after medical school. In addition to completing his residency in emergency medicine at Georgetown and George Washington universities, and earning a master’s degree in public health at George Washington, Dhindsa completed a fellowship in emergency medical service and served as assistant medical director for the District of Columbia Fire and EMS Department.

He joined VCU as EMS director in 1996 when the Department of Emergency Medicine was a newly established academic department in the medical school and, in 2001, he started VCU Health’s LifeEvac flight transport program. The flight program now includes three helicopters, a ground-transport component and a stand-alone dispatch center; it serves as a regional resource that performs interfacility transports as well as 911 scene response. In addition to his role as professor and department chair, Dhindsa continues to serve as medical director of the critical care transport team.

Under Dhindsa’s leadership, the department has created fellowships in emergency medical services, pediatric emergency medicine, ultrasound/resuscitation and education. In recognition of his contributions, he received VCU’s Outstanding Term Faculty Award in 2017.

“We also have a strong residency in emergency medicine and combined emergency medicine/internal medicine,” he says. “And we have a lot of emphasis at faculty and recruitment level on building diversity, equity and inclusion in the department.

“We are at the front door of the health system to our community. So it is important that we strive to provide culturally competent and sensitive care and that our work force reflects the population we serve. … I want us to be leading that effort for the health system.”

“I have never seen him not do whatever he can, in any situation, no matter how big or how small, to make things better for people.”

The worst day of their lives

VCU Health’s role as a safety net is unique in the region, as is its commitment to educating students, residents, fellows and other learners, from EMS providers to Navy SEALs. Still, for most of us, the emergency department is the last place we want to find ourselves. “One of the things you realize in emergency medicine is that you often are seeing people on the worst day of their lives,” Dhindsa notes.

He sees that encounter, however, as an opportunity not only to address his patients’ medical needs but to alleviate suffering in general.

“When people are at the lowest point of their life, it is important for them to realize they are not alone,” he says. “For patients and families, our ability to make that day better for them is really important. It is not necessarily the medical care that they will remember, but how we supported them through a crisis.”

For some, the crisis might be life-or-death: a heart attack, a stroke, serious injuries that require the attention of a Level I trauma center. For others, of course, it may be a more minor but still distressing complaint: a sprained ankle, norovirus, a laceration in need of stitches. The challenge – yet also the appeal – of emergency medicine, Dhindsa says, is to navigate these constantly shifting demands while serving all patients and families with authenticity and compassion.

“You have to be able to transition from resuscitating a trauma patient to taking care of a heart attack to going into a family room and notifying a family of a death of a loved one … and then, as soon as you step out of that family room, you have a line of other patients to attend to, and you have to immediately switch gears.”

It’s difficult work that takes an emotional toll. Staying resilient in the face of the suffering you bear witness to isn’t easy, Dhindsa says. “It can be a tough environment to work in.” Everyone has their own way of maintaining resilience, from spending time with family to enjoying the outdoors or participating in sports. Many find informal debriefings with peers who work in the ED – and who understand the environment and its challenges – to be the most therapeutic.

A crisis of disparities

One slow-burning crisis that is particularly challenging, Dhindsa says, is the steadily increasing pressure on emergency departments to treat problems our society has failed to address. Even amid the pandemic, more than 80,000 patients were treated in his emergency department last year. Among those were victims of gun violence; people living in poverty or with food insecurity or without access to primary care; the undocumented or homeless or mentally ill; and patients who keep returning to the ER because they have nowhere else to go. “These are people with needs who we as a society are failing,” he says.

To manage this pressure while continuing to provide optimal care, Dhindsa’s department has implemented changes to more efficiently see patients, reduce overcrowding and “keep patients who don’t need beds out of beds,” he says.

These changes include the Virtual Urgent Care clinic established during the pandemic, which is likely to continue. Prior to the pandemic, the flow model of the department was changed, with an attending physician placed in triage so that patients within minutes of arrival receive an initial evaluation, and workups such as bloodwork or imaging can be ordered. With the new model, walk-in patient wait times were reduced to 15 minutes or less on average.

Emergency and internal medicine faculty also have collaborated on establishing a ProPER (Providing Post-ER) Care Clinic for patients who have poor access to care and are at a higher risk for not following up or for being readmitted.

“We do a virtual telehealth follow-up visit one to three days after their visit,” Dhindsa explains. “We try to identify and address gaps in their health care and get them plugged into care coordination or social work or specialty care, and we have been able to prevent readmission for these patients.” Partnerships with the city of Richmond try to address the needs of patients who also have housing or food insecurity that impacts their health.

For Dhindsa, however, making a real difference means going beyond one patient at a time. in addition to earning an M.B.A. at VCU in 2007 – and now working on an M.A. in homeland security and emergency preparedness through VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School – Dhindsa has completed several leadership programs with a larger, systems-level effort in mind to address health disparities.

“How do we make sure these patients get what they need?” he asks. “Working clinically, you impact the patient in front of you. But if you move into a leadership position, your ability to influence change is that much greater.”

As a leader, Dhindsa has demonstrated that influence as a respected and sought-after expert serving on national committees developing standards for critical care transport, Baker says. His clinical skills, she adds, are exceptional. And he has received awards and accolades ranging from 1987 EMS Volunteer of the Year in Rockville, Maryland, to having been named a Richmond-area “Top Doc” by his peers, for excellence in emergency medicine, seven times since 2014.

But what Baker most deeply respects are Dhindsa’s commitment to the vulnerable and the compassion and dedication he brings to his leadership.

“I have never seen him not do whatever he can, in any situation, no matter how big or how small, to make things better for people.”