Finding a new perspective in anatomy

Alum-turned-priest-turned-teacher guides medical students through meeting their first patient

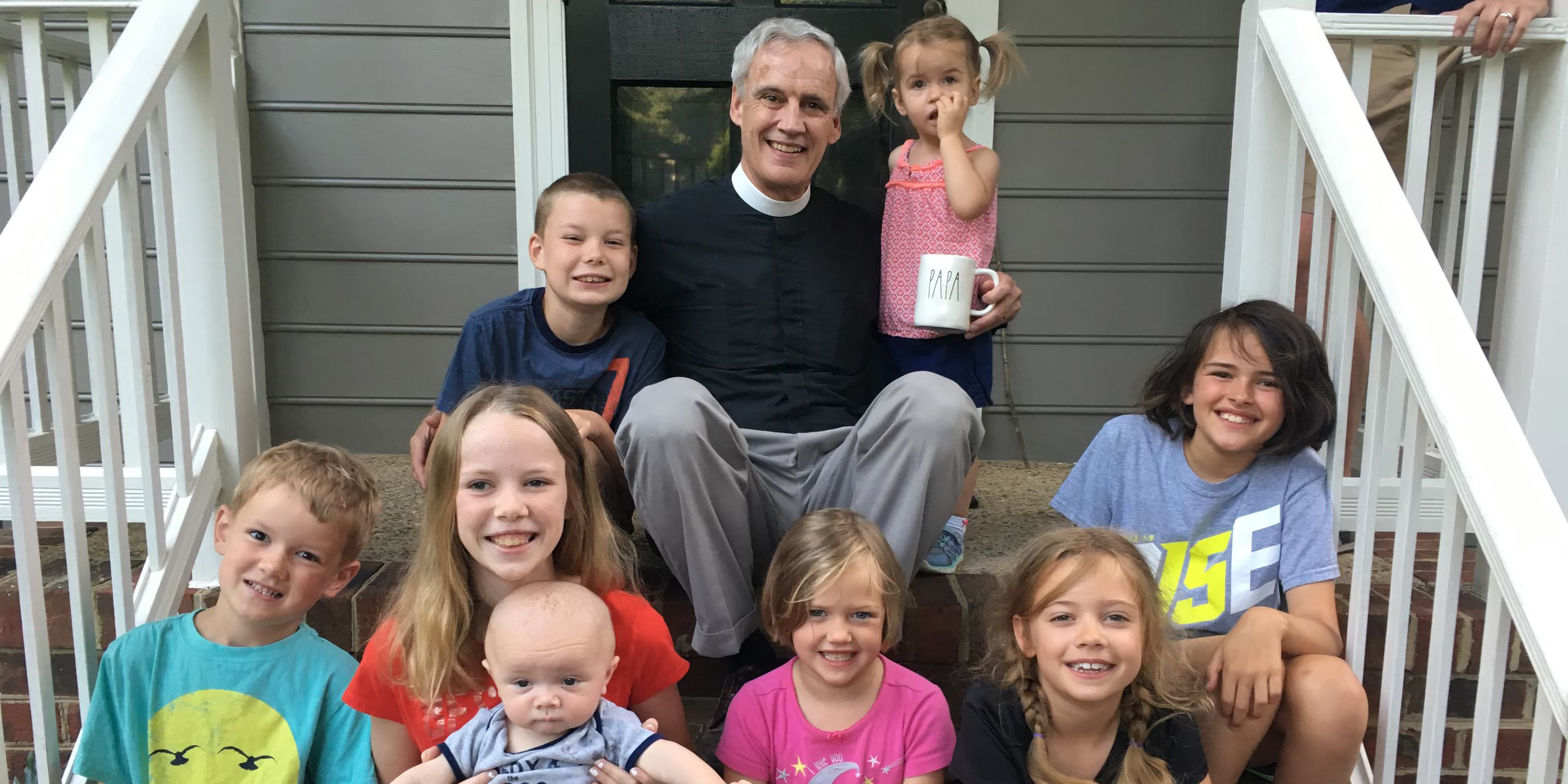

Charles “Chuck” Alley, PHD’77 (ANAT), and wife Scottie have three children and nine grandchildren, eight of whom were on hand for his last Sunday as rector at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church.

This story was published in the spring 2023 issue of 12th & Marshall. You can find the current and past issues online.

Most nonphysicians hearing the words, “You never forget your first patient,” likely envision a white-coated figure delivering a child, setting a broken arm or preparing to make the first major cut.

In truth, the first patient for VCU School of Medicine students is typically the cadaver, also known as the donor, in anatomy lab. That initial meeting can be a struggle. And that’s why Charles “Chuck” Alley, PHD’77 (ANAT), presents an introductory lecture, “Humanity of the Cadaver and the Physician,” to M1s. His job is to help prepare them for the reality of something not necessarily easy to face.

He is direct with M1s: “You will be presented with a human body. It will be a dead human body.

“Other than the initial human appearance – which under your hand will disappear rather quickly – you will be evaluated by the facts you glean, with no outward aids, challenged to deal with the cadaver as you would a living human. But no indications of pain, no reactions to conversation, no suggestions of symptoms.

“Yet these mute patients will reveal the secrets of their bodies and reveal previously unrealized secrets about yourself.”

Alley may be particularly suited to presenting the physical, moral and ethical sides of this experience. Completing his Ph.D. on the MCV Campus, pursuing a postdoc and teaching anatomy and research for several years elsewhere led to a conviction that “there was more to this thing than chance.”

Taking a few theology classes confirmed his interest – and, ultimately, his calling -- leading him to Virginia Theological Seminary in 1988.

Nearly three decades as an Episcopal priest included 23 years at St. Matthew’s in Henrico County outside of Richmond. While there, he reconnected with VCU, working with a community forum on religion and science on the Monroe Park Campus and serving as a primary reviewer on the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Upon retiring from the church in 2017, Alley accepted a part-time teaching position with the Department of Anatomy. “Anatomy is such a deep subject,” he says. “Students come across so many unexpected things. In a way, it’s a lot like theology. There’s such a depth to it.”

‘Our donor chose to be here because she wanted to teach us’

In 2018, Alley was asked to share a few words with anatomy students as they approached their tables, a job previously held by hospital chaplains. “No one passed out that year,” he chuckles, “which was kind of legendary.” Based on what he heard, professor Alex Meredith, PHD’81 (ANAT), asked Alley to begin officially offering lab introductions.

“The history of anatomical dissection exposes the difficult task you face during training,” Alley tells students. “Evidence of the drive for knowledge outstripping concern for people is staggering.”

Two R’s – respect and relationships – play a large part in Alley’s talks. Combining the cold hard facts with respect for patients, he notes, “will make you true healers of persons.”

During his lectures, he asks students to observe a moment of silence for victims of the drive for knowledge who involuntarily gave so much. Over the history of medical education, that has included the unclaimed remains of indigent people as well as the bodies of free and enslaved Black people robbed from their graves – including in Richmond for study on the MCV Campus.

Thankfully, Alley says, that is no longer the case. In recent years, the East Marshall Street Well Project has provided a forum for confronting the inhumanity of past practices and an opportunity to instill new perspectives.

“These patients have given themselves to you,” he says. “The donation is an intimate gift. It is a special relationship, an act of love on the part of the donor.”

M1 Alexis Dorsey gained valuable insight from Alley’s introduction. “When I first met our donor, I was sad thinking about her death. But the lecture helped me find a new perspective: that our donor chose to be here because she wanted to teach us.”

Communication – especially listening — is also key.

“Dissection is the art of asking questions about the human body, and the cadaver is the gift containing the answers,” Alley says. “It’s a gift that will provide you with the knowledge you need to succeed as a physician, a knowledge that goes beyond physical facts and to our attitude of gratitude for all bodies – healthy and diseased, whole and broken, pampered and abused, living and dead.”

M1 Guiliano Melki was initially uneasy when approaching his cadaver.

“But while making my first incision, I thought of Dr. Alley’s words. I realized I had to be thankful rather than apprehensive. I was going to be able to see and appreciate the complexities of what lies underneath the skin of a human being.

“A few short hours on my first day of anatomy lab flipped my entire perspective.”

The Virginia State Anatomical Program is authorized to receive donations of human bodies for scientific study and provides them to the state’s medical schools, colleges, universities and research facilities for the teaching of anatomy and surgery and medical research. Learn more about how to donate your body to science.