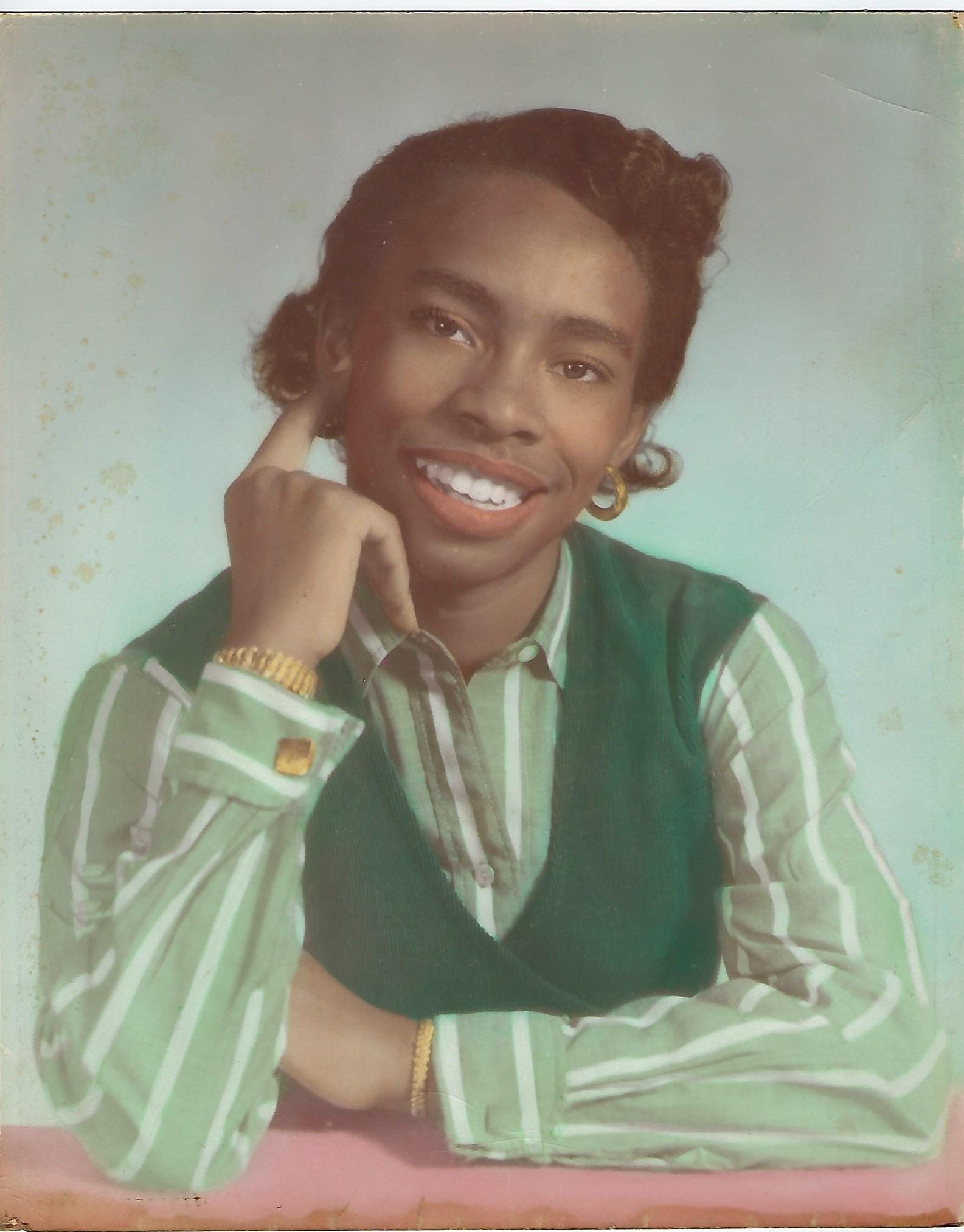

From a very young age, Norma Jean Goodwin, M’61, was determined to make a difference.

“It’s our obligation and responsibility to give back. That was drilled into us from the time we were very young,” explained Barbara Cuffie, Goodwin’s younger sister. “If you are the only one who reaps the rewards from your labor, then it really doesn’t mean anything. It’s only meaningful when you do something and give something back to help to make things better.”

This is a philosophy that Goodwin, who died last April, embodied throughout her career as she focused on improving health outcomes for African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans by addressing racial disparities. It also was an ideal she imparted to other physicians of color.

“It was like she was a little bit of a preacher, only it wasn’t The Bible she was preaching, it was your moral obligation, your responsibility,” Cuffie said. “You’ve got to share your knowledge and think about how it can make the world a better place.”

Following a dream

After graduating from Virginia State College at age 19, Norma Goodwin, M’61, followed her passion for medicine and was admitted to the Medical College of Virginia.

As a Black woman growing up in the segregated South, Goodwin understood all too well the realities of racial inequities. And having suffered with childhood asthma, she also knew “how important medicine was and how important it was to have doctors who cared about you,” according to Cuffie.

“From a very young age, she wanted to be a doctor, and of course, in my family, whatever you wanted to do, the family was supportive,” Cuffie said. “We grew up in a home where our parents always emphasized that you are only limited by your vision.”

Goodwin, who was always precocious, graduated from high school in Norfolk, Virginia, the same month she turned 15. She then went on to earn her undergraduate degree from Virginia State College (now Virginia State University).

According to her brother, Stefan Goodwin, Ph.D., “Norma was inspired by Jean Harris who in 1951 had been admitted as a student of medicine to the Medical College of Virginia” (now the VCU School of Medicine) and became the first Black person to graduate from the school in 1955. Just one year later, in 1956, at the age of 19, Goodwin followed in Harris’s footsteps to MCV to begin her medical education.

This was a decision that had far-reaching implications for the Goodwin family – especially for her father who was “literally driven out of business in retaliation for his daughter going to Medical College of Virginia,” according to Cuffie.

“He built 17 houses in the year before Norma went to medical school. He employed about 30-some men full time,” Cuffie recalled. “The newspaper in Norfolk wrote an article about Norma being accepted at MCV, and it caused a great deal of consternation and problems for him. He was basically told [by powerful men in the town]: ‘Do not try to integrate Medical College of Virginia, and if you do, you will pay. Anybody who gets you to build their house will not be able to get financing because you will have gone against the advice we are giving you.’”

Facing segregation in education

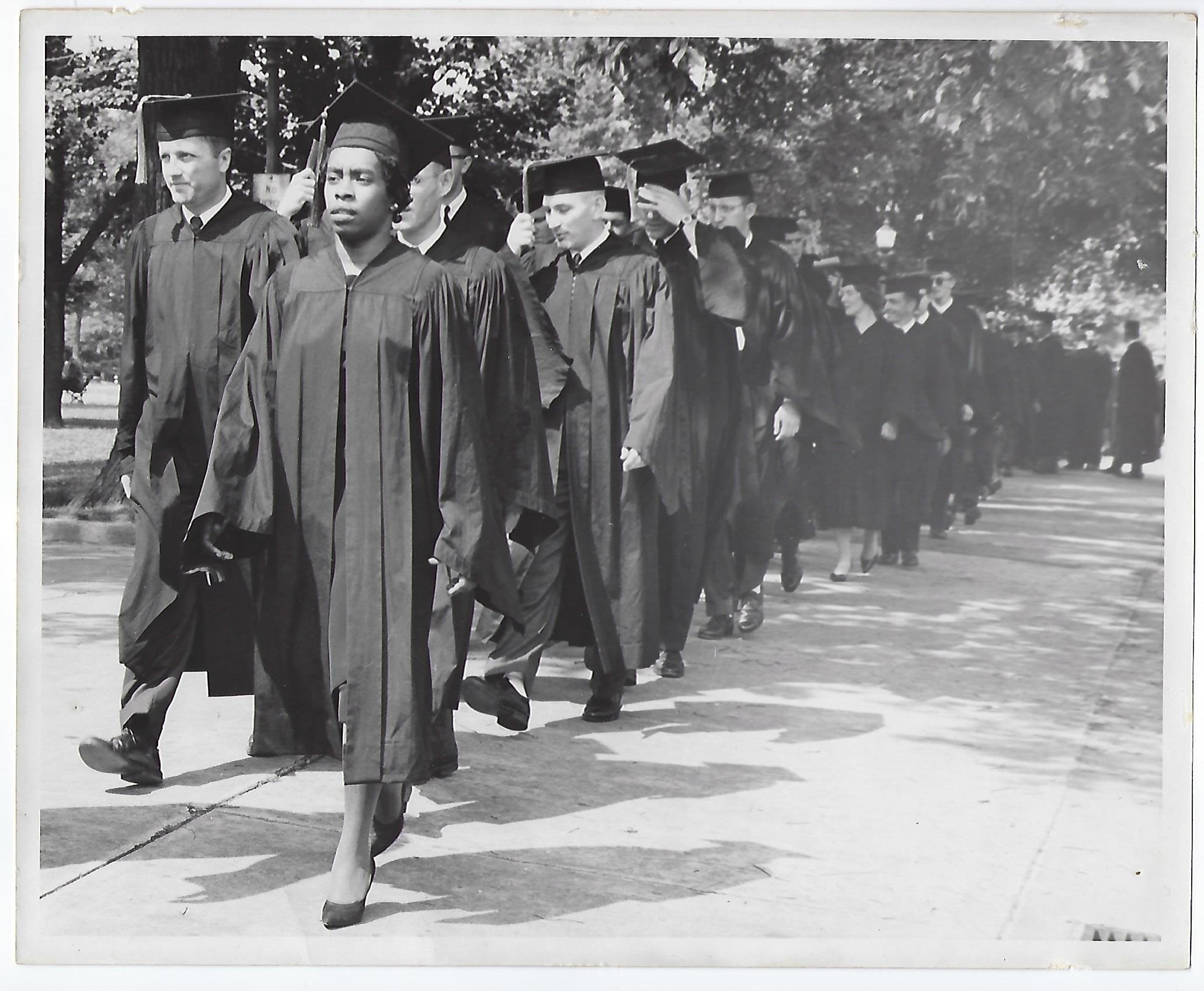

In 1961, Goodwin became one of the medical school’s first African American graduates.

For Goodwin, the challenges were only just beginning. She could not go through the same lunch line as the white students, had to reside in a dormitory designated for Black students attending the St. Philip School of Nursing – away from her white medical school classmates – and did her rotations at St. Philip and E.G. Williams hospitals, which treated Black patients.

When dissecting cadavers in class, all of the other students were divided into small groups; however, Goodwin was assigned to work alone. “She was expected to do, as an individual, what four people did otherwise,” Cuffie said.

Still, through everything she experienced – things that almost forced her to quit medical school – she remained committed to her chosen path.

“I can recall her being determined – extremely determined – that she wanted to do something to help humanity, and she felt that medicine was her thing and could not understand why she was treated the way she was when she was at Medical College of Virginia,” Cuffie said.

“Dr. Goodwin’s time on the MCV Campus were difficult years, made even more so by the segregation she was subject to,” said Peter F. Buckley, M.D., dean of the VCU School of Medicine. “And it pains me to know that Dr. Goodwin did not receive the support she deserved as she developed into the wonderful physician who made such a difference throughout her life. Her efforts inspire us to continue to strive for diversity, equity and inclusion in our School of Medicine and beyond.”

Making a difference through medicine

Goodwin was the founder, president and CEO of three businesses: Health Watch and Promotion Service, AMRON Consultants and Health Power for Minorities.

Goodwin’s experiences in Richmond propelled her north following medical school. She completed an internship at Kings County Hospital in internal medical and a residency at State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in nephrology.

At that point, “she never left New York. She never wanted to come back to Virginia to live because of the taste in her mouth from her experiences,” Cuffie said.

In the mid-1960s, New York City created the Health and Hospitals Corporation to replace its Department of Hospitals, which operated several city hospitals and other health care facilities. HHC was formed as a “quasi-public agency” to enable it to benefit from private revenues and funding as well as from government sources. As the senior vice president for community health and ambulatory care, Goodwin became HHC’s first female and first Black executive. She later served on the faculty of SUNY Health Science Center at Brooklyn and its M.P.H. program.

“Her real interest – her heart – was in trying to do something about the disparity between the health outcomes in minority communities versus Caucasian communities,” Cuffie said

This desire led Goodwin to found Health Watch Information and Promotion Service in 1984 and serve as its president and CEO for almost the next two decades. Over the years, the organization would support health education for underserved communities in Harlem, Bedford–Stuyvesant in Brooklyn and beyond on subjects ranging from hypertension, diabetes, cancer, HIV/AIDS, infant mortality, aging and stroke to teen obesity and national teen dating violence.

One of Health Watch’s most ambitious projects, spearheaded by Goodwin, was a one-day HIV/AIDS teleconference held at the New York Academy of Medicine that used closed-circuit links to connect approximately 10 other cities across the country.

When Health Watch dissolved in 2002, Goodwin launched Health Power for Minorities, a digital health news service that published blogs and stories written by a diverse group of doctors and health professionals. Healthpowerforminorities.com was among the top five Google sites for minorities and garnered more than three million hits annually.

Goodwin also founded a third company during her life: AMRON Management Consultants Inc., a health consulting firm that served more than 100 clients in New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Leaving a legacy

In March 2014, as Priscilla Mpasi, M’14, was completing her undergraduate medical education at VCU, she had the opportunity to meet Goodwin during a trip to New York.

“She told me how painful [her time in medical school] was and did not want anyone else to have the same experiences,” Mpasi said. “She took on leadership roles to try to bring about change. She paved the way for others.”

Goodwin served in leadership positions in numerous organizations, including the American Public Health Association, National Association of Health Services Executives, American Heart Association and American Red Cross of Greater New York as well as serving as an adviser to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. She also was the first woman and Black physician to be named vice president of the New York Hospital Association and chaired the task force that led to the creation of the National Medical Association’s Council on Concerns of Women Physicians, a council Mpasi now co-chairs.

“It was just a part of who she was – going to the National Medical Association conventions every year and always having some kind of presentation where she was sharing information with other doctors, mostly African American,” Cuffie explained. Goodwin would often talk about “their responsibility for trying to make a difference.”

These conversations resonated with many, including Mpasi.

“If we all work together, we can understand the barriers to delivering equitable care,” Mpasi said. “We all have a responsibility to ensure everyone receives the care they deserve. Dr. Goodwin knew that and lived it. I just hope I can make her proud.”

Goodwin died on April 13, 2020, one month before she would have turned 83, after becoming ill with COVID-19 and developing pneumonia.

“Although she no longer walks among the living, a large part of her legacy is the courageous fight which she led against life obstacles which were personal as well as those associated especially with communities which were underserved by America’s health care system,” her brother Stefan wrote. “Throughout her life, she was steadfast in her pursuit of excellence, of equal opportunity and of justice.”