In 2005, surgeons in France completed the world’s first partial face transplant on a woman who lost her lips, cheeks, chin and most of her nose after she was mauled by her dog.

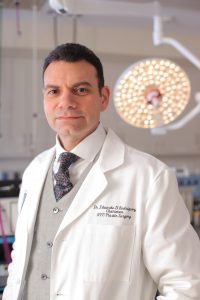

A dozen years and many lessons later, face transplantation has moved from possibility to reality, with surgeons refining techniques and transforming the lives of patients once considered beyond hope. Leading the way is Eduardo D. Rodriguez, M’99, considered one of the world’s pioneering surgeons in the field.

This story first appeared in the spring 2017 issue of the medical school’s alumni magazine, 12th & Marshall. You can flip through the whole issue online.

EDUARDO D. RODRIGUEZ, M’99, returned to the MCV Campus last summer as the speaker for the 2016 S. Dawson Theogaraj Lecture. At the annual event, he described his team’s work to complete the most extensive face transplant ever. Rodriguez is the Helen L. Kimmel Professor of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery and chair of the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic Surgery at New York University’s School of Medicine. The surgery, which took place at the NYU Langone Medical Center in August 2015, received extensive media coverage and cemented Rodriguez’s reputation in the field.

Patrick Hardison, a 41-year old firefighter from Mississippi who had received horrific facial injuries, received the face of David Rodebaugh who had died in a cycling accident. The operation included a number of milestone procedures including transplanting the donor’s eyelids and muscles that control blinking – which had not been previously performed on a seeing patient. In addition, the ears and ear canals were transplanted along with bony structures, including portions of the chin, cheeks and the entire nose.

Rodriguez credits his time in VCU’s School of Medicine for a solid foundation in medicine. Rodriguez earned a D.D.S. degree from New York University in 1992, then completed his residency in oral and maxillofacial surgery at Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

“There are oral surgery programs that have affiliations with a medical degree, and I had colleagues who recommended that this was something I should do. I applied to all the medical schools in the country that had a relationship with an oral surgery program.” He ended up at VCU, condensing his medical degree into two years. After that, he trained in the plastic surgery program at Johns Hopkins Hospital/University of Maryland Medical Center and completed a fellowship in Taiwan.

“I thought VCU was the best education I ever received,” he said in a telephone interview from New York. “Those were the most enriching educational years of my life. I became a very good student. Living in Richmond, a smaller town, allowed me to focus on education and gave me a very strong foundation to be successful.”

Rodriguez first became interested in the possibility of face transplants after hearing a lecture at Johns Hopkins about face transplants in rats. “My mentor at Johns Hopkins, the chief of plastic surgery, told me this is what I should be doing. I had no idea what that really meant, but I was fascinated by it.”

Rodriguez first became interested in the possibility of face transplants after hearing a lecture at Johns Hopkins about face transplants in rats. “My mentor at Johns Hopkins, the chief of plastic surgery, told me this is what I should be doing. I had no idea what that really meant, but I was fascinated by it.”

Before joining NYU Langone in 2013, Rodriguez was on faculty at R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. There he led a 2012 landmark surgery, the most extensive facial transplant at the time, of a Virginia man who had suffered a gunshot wound.

ENDOWED LECTURESHIPS SPARK NEW IDEAS AND APPROACHES

At the time of the death of S. Dawson Theogaraj, M.D., in 1984, a fund was established with gifts from a variety of sources to honor the life and work of the plastic surgeon who was known for his academic brilliance and dedication to teaching. The fund supports an annual lectureship program as well as an award to the plastic surgery resident who achieves the highest score on the plastic surgery in-service exams.

The lectureship is one of about two dozen in the medical school supported by endowed funds at the MCV Foundation. The funds carry the names of some of the school’s best-known faculty, alumni and friends including: renowned orthopaedic surgeon Richard Caspari, M.D., who advanced arthroscopic surgery and treated Mary Lou Retton six weeks before her gold-medal-winning Olympic performance; Clarence Holland, M’62, who served his community as a family physician for 42 years and as a Virginia state senator for more than a decade; and the pioneering medicinal chemist and faculty member Everette May, Ph.D., who synthesized an anti-malaria drug as well as a drug still used as an alternative to methadone treatment for opioid addiction.

The medical school’s lectureship endowments, totaling more than $2.7 million, enrich the MCV Campus’ learning environment for students, residents and faculty by bringing important topics and innovative thinkers to campus. In addition to Eduardo Rodriguez, M’99, serving as the Theogaraj Lecturer, recent years have seen highly regarded speakers from all over the country visit Richmond to share advances, technologies and perspectives that shape future approaches to patient care, scientific discovery and medical training.

Rodriguez notes that such transplants include health and mental risks that must be weighed against the benefits. Recipients deal with the psychological battles of living with someone else’s face, as well as lifelong reliance and side-effects of immunosuppressant medicines. As with other transplants, the body can reject a new face.

In such a developing field, he notes, there’s not yet a blueprint for success.

“Physicians and patients are on this journey together,” he says. “Once you’re successful and you see the patient doing well and you reflect on what we’ve achieved, and reflect on change in this individual’s life, you can’t help but be amazed by the complexity of the process.”

The Department of Defense and several research institutions, including NYU, have dedicated funding and resources to refining the procedure.

Rodriguez knows that the next decade will include improvements in transplantation and perhaps even some breakthroughs that seemed unimaginable in recent years.

“First, we have to keep working on trying to reduce the toxic effects of the anti-rejection medicines,” he says. He believes biomedical engineers will one day be able to create tissues specifically for patients needing transplants.

“It’s not just how many more transplants I can do. It’s how can we continue to improve the quality of face reconstruction and bring in different elements of science to provide these types of procedures safely, as well as improving the quality of these patients’ lives and shaping a better future for these individuals.”

By Lisa Crutchfield