The Class of 53’s Julie Møller Sanford.

There’s a Danish proverb that says “Alle Baader hioelpe.”

“Every little helps.”

Julie Møller Sanford, M’53, discovered at a young age that a little kindness could go a long way.

Born in Alabama to Danish parents, Møller and her family lived in Copenhagen, Denmark, for much of her childhood, enjoying the company of aunts, uncles and cousins who lived within walking distance. Yet all of that quickly changed in April 1940 when Germany invaded Denmark during World War II.

Møller was just 13 years old.

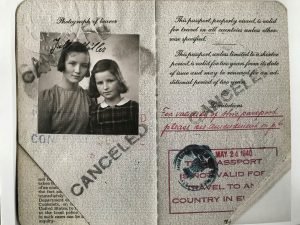

At the time of the invasion, her parents were overseas so, alone, she and her 10-year- old sister fled through Germany, Austria and Italy to catch a boat to New York. Although they were able to travel under an American passport, their journey wasn’t without peril. Germany had invaded the Lowlands in Western Europe and as the sisters reached the Brenner Pass between Austria and Italy, the border closed. German soldiers marched on their train and turned it back to Innsbruck, Austria, forcing all passengers from the train.

“Despite maintaining a calm facade for the sake of her little sister, my mom was scared to death,” says Møller’s daughter, Ann Sanford, recounting the stories her mother shared with family before her passing in 2017. It wasn’t until adulthood that she and her siblings learned many of the details of what happened, thanks to Møller’s inquisitive grandchildren.

The Møllers’ dearest family friends in Denmark were Jewish and “she had heard of the concentration camps and didn’t know what would happen as she sat with her sister on the train platform in Austria,” Sanford says. “Then a kind young man took notice and helped them find food and a place to stay. The next day, they were able to get back on the train and continue their journey.”

The Class of 53’s Julie Møller Sanford and her sister were passengers on one of the last ships to safely reach the U.S. during WWII.

Ultimately the sisters reached the boat in Genoa, Italy — one of the last passenger ships to safely cross the Atlantic Ocean. At last safely aboard, Møller recognized the dire circumstances around them; they were fortunate to share a cabin with an elderly woman while many passengers slept in common areas.

Their mother met the boat in New York City with tears of relief and joy, having searched for them on each ship that arrived.

“The impact of that period in her life helped her understand the hardships faced by many and the difference one person could make,” Sanford says. “She also was mindful of and grateful for the opportunities she had for learning and to make a positive contribution. She just appreciated life. In her medical practice and in her community, she was calm and resourceful, kind and accepting. She understood the importance of recognizing the dignity in others, whatever their origins or circumstances.”

So it came as no surprise to Sanford that her mother decided to endow a scholarship in the School of Medicine. In coordination with her husband John Sanford, also a physician, she made provisions for the MCV Foundation in her estate and also named the foundation as a beneficiary on her retirement accounts.

“My parents had families that supported them when they worked to become physicians — emotional support and financial support,” Sanford says. “They appreciated that and wanted to pay it forward. Medicine wasn’t just a job or profession to them. It was a calling and an opportunity to make an impact. Both viewed this scholarship as a wonderful way to continue that work, their life’s work, and to share that with others.”

Møller also had an impact in Duluth, Minnesota. In 1964 she became the first female doctor at the Duluth Clinic, where she practiced internal medicine. Sanford remembers pictures from her mother’s early years of training in Chicago and in practice — all men and “then there’s mom. Women in medicine were all pioneers back in those days.”

Møller made a point to treat each patient as an individual — not a lab result or diagnosis, a lesson she passed on to the two of her four children who became physicians and to her students in her role as a clinical preceptor for the University of Minnesota Medical School in Duluth.

“My brother told me of her advice to him — to make sure to find out something personal about each patient,” Sanford says. “What’s the most exciting thing they’ve ever done or the most beautiful thing they’ve ever seen? And then remember it. Treat each patient as a unique person, with dignity and respect.”

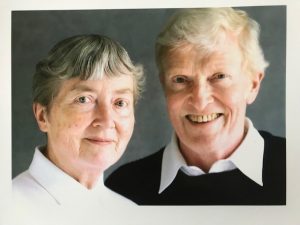

The Class of 53’s Julie Møller Sanford and her husband John Sanford, M.D.

Both lifelong scholars, Møller and her husband instilled a love of learning in all their children, as well as an appreciation for their Danish heritage. Their home was always “hyggeligt” — cozy and welcoming, filled with family, friends and plenty of books.

This warm and accepting spirit, impressed upon Møller by the experiences of her childhood, now extends to the School of Medicine and future scholarship recipients. To Julie Møller and John Sanford, the commitment was about more than money.

“My sister, a physician, summed it up well noting that our parents would have said to the students, ‘It’s us next to you. We’re here for you and we believe in you,’” Sanford says.

“That’s just how they were. All four of us kids are so proud and happy that they were able to do this. Our family will grow with this scholarship.”

Planned giving donors like Julie Møller Sanford, M’53, help shape the future of the MCV Campus. In addition to including the MCV Foundation in her estate plan, Møller also named the foundation as a beneficiary on her 401k and IRA accounts.

“Using a retirement account is such an easy way to include a charity in your long-term plan,” says Jane Garnet Brown, director of gift planning at the MCV Foundation. “There’s no need to update your will or work with a lawyer, and the beneficiary designation can be made anytime.”

Retirement assets are generally included as a taxable estate asset and taxed as income to the named beneficiary. As a result, your beneficiary may ultimately receive only a fraction of the account’s value.

“By naming the medical school as your beneficiary, you can avoid these taxes entirely with 100 percent of your gift supporting your charitable intentions and thus leave more tax-efficient assets to your beneficiaries,” Brown says. “It’s certainly another tool to consider in your estate and philanthropic planning, especially if you have other ways of providing for your loved ones.”

Planned gifts are one way to support the School of Medicine’s 1838 Campaign, which aims to increase the number and size of scholarships to students. Full- and half-tuition scholarships, created with a commitment of $750,000 or $375,000, are most urgently needed and serve as one of the medical school’s best resources for recruiting and rewarding top students.

The MCV Foundation houses the medical school’s endowment funds and offers planned giving expertise to our alumni and donors. If you want to begin a conversation about how to use estate planning to your advantage, please call Jane Garnet Brown at (804) 828-4599. If you are already speaking with a representative from the School of Medicine about making a gift, please let them know you’ve seen this article and would like more information.

By Polly Roberts