Twenty years after the closing of Skull and Bones, Edward “Eddie” Shaia can still rattle off the Friday specials like it was yesterday. “Soup of the day was clam chowder. Then we had lake trout, turnip greens and mac ‘n’ cheese.”

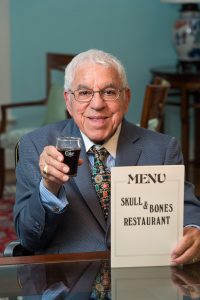

Edward Shaia managed

the beloved Skull and

Bones for 50 years.

When Shaia began managing the restaurant with his brother, Richard, in the 1950s, a 6-ounce glass of Coke cost a nickel. He remembers when the supplier tried to upsell them a larger size for 10 cents a glass. “We thought, ‘Who would ever drink that much Coke?'”

Now in the days of Big Gulps and super-sized meals, Skull and Bones is reminiscent of a different era. Lured by fresh limeades and made-from-scratch onion rings, the steady flow of customers made the restaurant an MCV Campus favorite. “Different people would come in to find out what was going on around the hospital and the city,” says Shaia, now 94. “The Skull” was the place to see and be seen.

The restaurant’s seats stayed full with physicians dining on chicken salad sandwiches and homemade soups, medical students drinking those extra thick milkshakes to celebrate passing a test or patients and their families stopping in for a bite after an appointment at the hospital. Lorraine Arias, M’83, remembers one attending physician who held Friday afternoon check-out rounds at Skull and Bones. “And he would always pick up the tab!”

Like many School of Medicine alumni, the restaurant holds a special place in her heart. “During the winter of my M2 year, a group of us got together there and my future husband-to-be and fellow M2 classmate, Jim O’Brien, joined in. After a casual lunch, he and I lingered under the guise of studying, and we’ve been together ever since.”

The couple married in 1982 and frequently met for lunch at Skull and Bones, first when they found themselves on different clinical rotations and later when they lived in an apartment on nearby Clay Street. “Skull and Bones continued to hold a prominent role in our lives.”

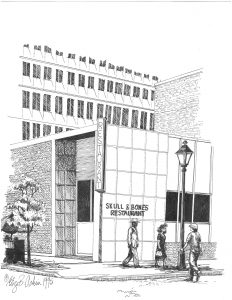

This pen and ink drawing was created by Richmond illustrator Eliza B. Askin. She recalls, “My brother was born at MCV while my father, who was a resident at the time, was eating at Skull and Bones. My mother never forgave him!” Both that newborn as well as his brother went on to graduate from the School of Medicine.

Shaia smiles when he hears the story. He knows of at least one couple who got engaged at the restaurant whose popularity spanned generations.

Today, the medical school’s alumni and development officers travel the country (get to know them on page 36); they say Skull and Bones is one of the most common, and cherished, memories shared by alumni. “Everyone has a story about Skull and Bones,” says Amy Lane, director of major gifts in the medical school. “But my favorite is from the Class of 57’s Bill Kinzer. The restaurant was so crowded it forced a chance meeting with his future wife, Kitty, who asked to join him at his two-person table during lunch — and a spark was lit.”

When the restaurant closed in the late 1990s to make way for the Gateway Building, which connects Main Hospital and Nelson Clinic, regular customer and faculty member G. Watson James III, M’43, H’46, even penned a poem: “Let us lament the loss of the SKULL …”

Shaia attributes the restaurant’s success to location, affordable prices, a robust sandwich selection, and yes, those famed onion rings (never frozen) and limeades (he ordered 500 limes a week to satisfy the craving of thirsty customers).

More than that, Skull and Bones was a family affair and customers appreciated the warmth of the Shaia clan. The family recalls how Eddie’s father, Harry, got it all started, opening The Medical Inn on the MCV Campus. Through the Great Depression and over the next few decades, it took various names in various locations, evolving into Skull and Bones at the corner of 12th and Marshall.

Brothers Eddie and Richard carried on the tradition when Harry Shaia semi-retired in the 1950s. Harry died in 1980 and Richard later left to go into real estate, but Eddie stayed and eventually brought on his daughter, Bernadette, to help manage the restaurant. At different points over the years, all of his and wife Marie’s eight children took a turn at working for the family business.

The restaurant’s enduring legacy comes down to its people — generations of the Shaia family who made Skull and Bones the welcoming hot spot of its day, and the generations of customers who faithfully walked through its doors.

By Polly Roberts