What a difference a century makes! Knowing the School of Medicine’s modern day 50-50 mix of men and women – right in sync with national numbers – it’s startling to remember that the first female medical students didn’t arrive on campus till 1918, three women among a class of 42.

At the time, 80 years after the school’s founding, admitting women to medical school was intended as a stopgap measure resulting from the dearth of available male applicants during World War I. As it turned out, women made excellent students and physicians. Whether they were actually welcome to the party during the next 10 decades varied considerably from person to person.

Women comprised as little as 2 percent and as much as 13 percent of each graduating class till about 1980, when the number jumped to 30 percent and continued to climb. That’s primarily because the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics was advising college career counselors to expand their range of recommended occupations for women. Traditional fields could not absorb the increased number of college graduates. Thus enrollment in professional (and traditionally male) programs saw unprecedented numbers of female applicants. Added to that were 1960s racial unrest, antiwar sentiment and student activism, fueling young people’s interest in careers involving public service. Fast forward to 2018. “The percentage of women entering medical school today is a huge accomplishment,” says Kimberly Sanford, M’01, H’06.

Sanford is an associate professor in the School of Medicine’s Department of Pathology with educational and clinical responsibilities. “Women have reached equality in terms of the number accepted into medical school nationally,” she says. “But we do not see that same acceptance into upper-level or executive medical positions. In addition, there are still problems with inappropriate behaviors and comments of a sexual nature directed to women. These two issues are the biggest problems facing us today.”

To pay tribute to these trailblazers who’ve made their alma mater proud, we talked to School of Medicine alumnae from the past seven decades. Some of their experiences will sound familiar; others will not. Ironically, the racial unrest and prejudice that inspired some students to go into medicine also created major issues for black female students, the first of whom was admitted in 1951. Many thanks to the following alumnae for sharing their individual perspectives. They represent thousands of accomplished women, pioneers in a profession that had been closed to them for hundreds of years.

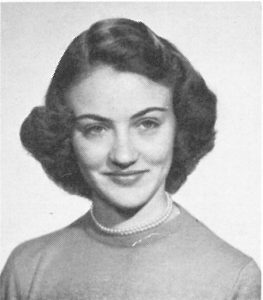

DOROTHY URBAN WRIGHT, M’56, Syracuse, New York

The first time Wright noticed disparate treatment for women was when classmates divided into homecall groups. “Boys who I thought were fond of me didn’t want me in their group,” she says. That came as a surprise.

In general, however, Wright was more conscious of racial discrimination in the segregated South than of gender disparities. Blood banks, for example, were separate.

As third year ended, she and her husband, neurologist A. WILLIAM WRIGHT, M’53, welcomed a baby boy. Because men weren’t traditionally encouraged to do housework, it was only late in the evening, after cooking and cleaning, that she could study.

Following an internship, Wright settled into her career as a pediatrician. “I have a lot of guilt about leaving the four children with caregivers. Eventually, they allowed people to do residencies part-time, which would have been ideal.”

Wright, whose husband died in 2004, retired from practice at age 80. “I still miss it terribly,” she says. “It’s in the blood.” But her legacy continues. Before retiring, Wright began a palliative care unit at her hospital, where she still volunteers. And her daughter – who at age 16 accompanied her parents to Haiti for a monthlong mission at Albert Schweitzer Hospital – is now a physician.

MARGARET “PEGGY” ZEE JONES, M’61, H’66, East Lansing, Michigan & Gainesville, Florida

YVONNECRIS SMITH VEAL, M’62, St. Albans, New York

Margaret Zee Jones, M’61

Jones recalls an uncomfortable discussion with her undergraduate alma mater’s dean of medicine, who said, “We always take a few women students to improve the decorum of the class.”

Instead, she matriculated at MCV, where she found that most students and professors were absorbed in their work and their lives. “They weren’t involved in making life difficult for others.”

But years later, Jones worries that her own preoccupations blinded her to the difficulties faced by Veal, her only black female classmate.

After Jones married JOHN W. “JACK” JONES, M’57, H’61, she felt classmates were acting a bit distant. But her experience didn’t compare with Veal’s, who found that her gender or race – or both – could be problematic.

Veal recalls receiving markedly different treatment from two male professors, one of whom would not pass her after second year. Graduation was delayed, and funding was difficult.

“You can hurt me for just a little while,” Veal philosophizes, “but you’ll never stop me from trying to do what I feel is right.” Still, it did hurt when it came time to select home-call groups, and the men exercised their option of refusing a woman or black student. That hadn’t changed since Dorothy Wright’s experience in the ’50s.

Yvonnecris Smith Veal, M’62

Fortunately, there were exceptions among Veal’s fellow students, like Jones, whom Veal remembers as “nice and helpful.” When some classmates changed seats rather than sit next to Veal, Jones would come and sit beside her.

Veal found neither gender nor race to be issues as she entered her practice in New York. She was named a fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1996. In 2009, she retired as senior medical director for the U.S. Postal Service from a career that included serving as president of the National Medical Association, the largest and oldest national organization predominantly representing physicians and patients of African-American descent.

Jones, who retired after 30 years as professor of neuropathology at Michigan State University, earned her M.Div. degree and spent several years as a board-certified hospice chaplain and ordained elder in the United Methodist Church.

Nearly six decades after graduating, the two former classmates have reconnected, to their mutual excitement. Jones still wishes she had been more fully aware of Veal’s circumstances. “Peggy,” Veal responds, “graduating with an M.D. degree from MCV is one of my proudest life accomplishments. And yes, you were part of my sustaining recipe.”

REBECCA M. “BECKY” BIGONEY, M’79, H’83, Fredericksburg, Virginia

A college guidance counselor advised Bigoney, who had wedding plans, not to tell medical school admissions committees for fear of rejection.

“There was a fair amount of feminist sentiment, but it was still very sexist,” Bigoney says of the ’70s.

Once Bigoney arrived on campus, she says, “Women had a sense of camaraderie and feeling fortunate we got in.” That’s also around the time applications started climbing.

In the classroom, Bigoney recalls, “You were on your own. You sank or swam on your own merit.” If a professor made a questionable comment or exhibited behavior that was construed as sexist – such as the anatomy professor who used photos of Playboy Bunnies as illustration – female students felt free to “get angry, shout them down or walk out.”

Classmates were respectful and friendly, and the female faculty she knew were accomplished yet approachable. But the expectation was that “women would go the community or practice route rather than academe.”

An internal medicine physician, Bigoney credits J. THOMAS RYAN, M’72, H’75, as a mentor who encouraged her to volunteer for leadership assignments. Her career more recently took an unexpected but satisfying turn when she accepted the first administrative position leading to her current role as executive vice president and chief medical officer for Mary Washington Healthcare.

JACALYN B. BLACKWELL-WHITE, M’84, Windsor Mill, Maryland

When Blackwell-White applied to medical school, she was about 10 years older than the typical first-year student. Discouraged by a professor in pre-med, she had switched to psychology.

Jacalyn Blackwell-White, M’84, at graduation with her mother.

But still wanting to be a physician — and despite hearing that medical schools “don’t want you encumbered” (i.e., married with children) – she requested an interview.

“MCV had a reputation as being a good ol’ boys school,” recalls Blackwell-White. As an African-American, her heart sank when she met the interviewer. “He looked so much like Col. Sanders!”

Instead of discouraging her, however, then-Dean of Admissions MILES HENCH, PH.D., was encouraging … and honest. “He looked at me and said something like, ‘You have a hard road to travel. But if you really want to do this, put in an application!’”

Hench and others on campus were supportive of the few African-American students, and Blackwell-White doesn’t recall negativity from classmates.

That wasn’t always true of faculty or patients; as Yvonnecris Smith Veal had found in the ’60s, it was hard to tell if they were reacting to Blackwell-White’s gender, race or both. Occasionally patients weren’t keen on her treating them. She was delighted whenever she changed their minds. One such patient at the McGuire VA Medical Center, after she worked with him, “even gave me a gift!”

Following an internship and residency in Massachusetts, she returned home to Maryland as a practicing pediatrician.

LIBBY Y. KOT, M’94, Hattiesburg, Mississippi

As a female medical student in the early 1990s, Kot “didn’t feel any distinction at all. The faculty were there to teach you. They had a vested interest in producing good doctors.

Libby Kot, M’94, with husband James Kot, M’94.

“You have to be able to function under stress, but I met the most amazing people!”

Those amazing people included her husband-to-be, cardiothoracic surgeon JAMES KOT, M’94. Their whirlwind fourth year included matching, graduating and getting married, all within a matter of weeks, then moving to New Orleans, where she completed her OB-GYN training under TOM NOLAN, M’77.

It wasn’t till she began practicing in Mississippi that Kot saw a difference in attitude. “New Orleans is such a mishmash, nobody thought twice about gender,” she says. “But here in Hattiesburg, it was more traditional, with disproportionately fewer female physicians.”

Or maybe, she speculates, it was more evident in community hospitals than in academic medical centers. In 2001, she was one of two women OBGYNs among 300 full-time physicians at Hattiesburg Clinic. For patients, “the thought of seeing a female OB-GYN seemed weird at the time.”

Now, she says, “The younger generation seems to prefer female gynecologists. And at the clinic, about 45 of our 350 full-time physicians are women.”

ELIZABETH “LIBBY” SHERWIN, M’05, Washington, D.C.

By the time Sherwin hit campus in the early 2000s, medical school classes were approaching 50-50 in terms of gender.

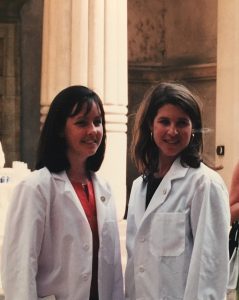

Libby Sherwin, M’05 (left), and Becca Clary, M’05, on their White Coat Ceremony day, 2001

She feels fortunate in having quickly found a group of eight “really tight, really amazing women who are great role models and still some of my best friends.”

The group worked and studied well together; competition was not a factor. Though Sherwin has experienced gender differences at times throughout her medical career, she does not recall gender bias or significant differences during medical school. She appreciated the support of great faculty mentors, including the now-retired CYNTHIA HELDBERG, PH.D., associate dean for admissions, and LINDA COSTANZO, PH.D., who was then assistant dean for pre-clinical medical education.

Since becoming an attending physician and practicing at different hospitals, she has heard male colleagues say they’re aware that women have to work two to three times as hard to be seen as equals.

A pediatric cardiologist and electrophysiologist with Children’s National Health System, she notes practical differences still exist, such as making allowances for women who are breastfeeding. “It’s not negative, it’s just reality.”

Last year, her tight-knit medical school group attended her wedding. Missing was REBECCA CLARY HARRIS, M’05, who died in 2007. Inspired by Harris’ example, the group created a scholarship in her name. “Her personality and light should live on,” Sherwin says.

ESTHER M. JOHNSTON, M’11, Seattle, Washington

Esther Johnson, M’11

Reflecting on her medical school years, Johnston doesn’t remember her gender being the dominant force impacting her education. “In fact, from my graduating class – thinking of historically male-dominated professions like surgery – that year, the surgical intern class was all female!”

Johnston is director of family medicine programs and interim chief medical officer for Seed Global Health.

The challenges faced by today’s women in the workplace, she feels, are often structurally and societally based. “When female physicians have children, the lost time and lack of resources can set women back.”

She does see a difference in how people perceive female leaders in the medical profession and hopes that will change over time. Citing the Implicit Association Test, which measures hidden gender and racial bias, Johnston says, “When we take the effort to make ourselves aware of biases, then we make the effort to change them.”

Be it classroom or workplace, that’s how progress is made.

EDITOR’S NOTE

In honor of the medical school’s 100 years of women, 12th & Marshall is pleased to share these alumnae stories. We appreciate that they were frank with us, telling us about both the good and the bad. Your experience might have differed. We hope you, too, will share your story with us at MedAlum@vcu.edu. As our alumnae noted, they are grateful for the opportunity to have studied medicine. But gender discrimination and sexual harassment have been and continue to be issues in medicine just as in society. We hope all of our readers will take the challenge offered by ESTHER JOHNSTON, M’11, to be aware of our biases and change them. Recent reports from the AMA, the National Academy of Sciences and others shed light on the issue and offer guidance in addressing it:

• JAMA Perspective: Sexual Harassment in Medicine — #MeToo

• AMA Wire: Medicine must address #MeToo moment—and beyond

• ACP Hospitalist: Medicine’s #MeToo movement

• The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine: 2018 report Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

• Implicit Association Test measures the strength of associations between concepts and evaluations or stereotypes