Miles Hench, Ph.D., knew what it was like to overcome challenges. A child of the Great Depression, his father's job as a traveling salesman landed Hench in 13 different schools from kindergarten through high school. Because his family moved so often, his mother struggled to hold down a steady job as a nurse.

Do you have a favorite memory of

Miles Hench, Ph.D., and how he impacted your medical school career?

Email us at MedAlum@vcu.edu and share your story.

The constant change put a strain on the young Hench, says his daughter, Carol Valentine.

"He missed out on a lot of the things that you participate in if you're at the same school for a long time," she says. "He had trouble sustaining friendships. He always felt like he was catching up.

The experience stuck with him as he went on to fight in World War II, earn his Ph.D. in microbiology and later join the faculty at Medical College of Virginia, where in 1961 he became chair of the medical school's admissions committee and ultimately served as dean of admissions until his retirement in 1982.

Hench, who died in 2001, never forgot what it was like to be an underdog. It earned him a reputation for discovering potential others may have overlooked in medical school applicants.

"His credo in life was 'everyone has value,'" Valentine says

'He changed my life'

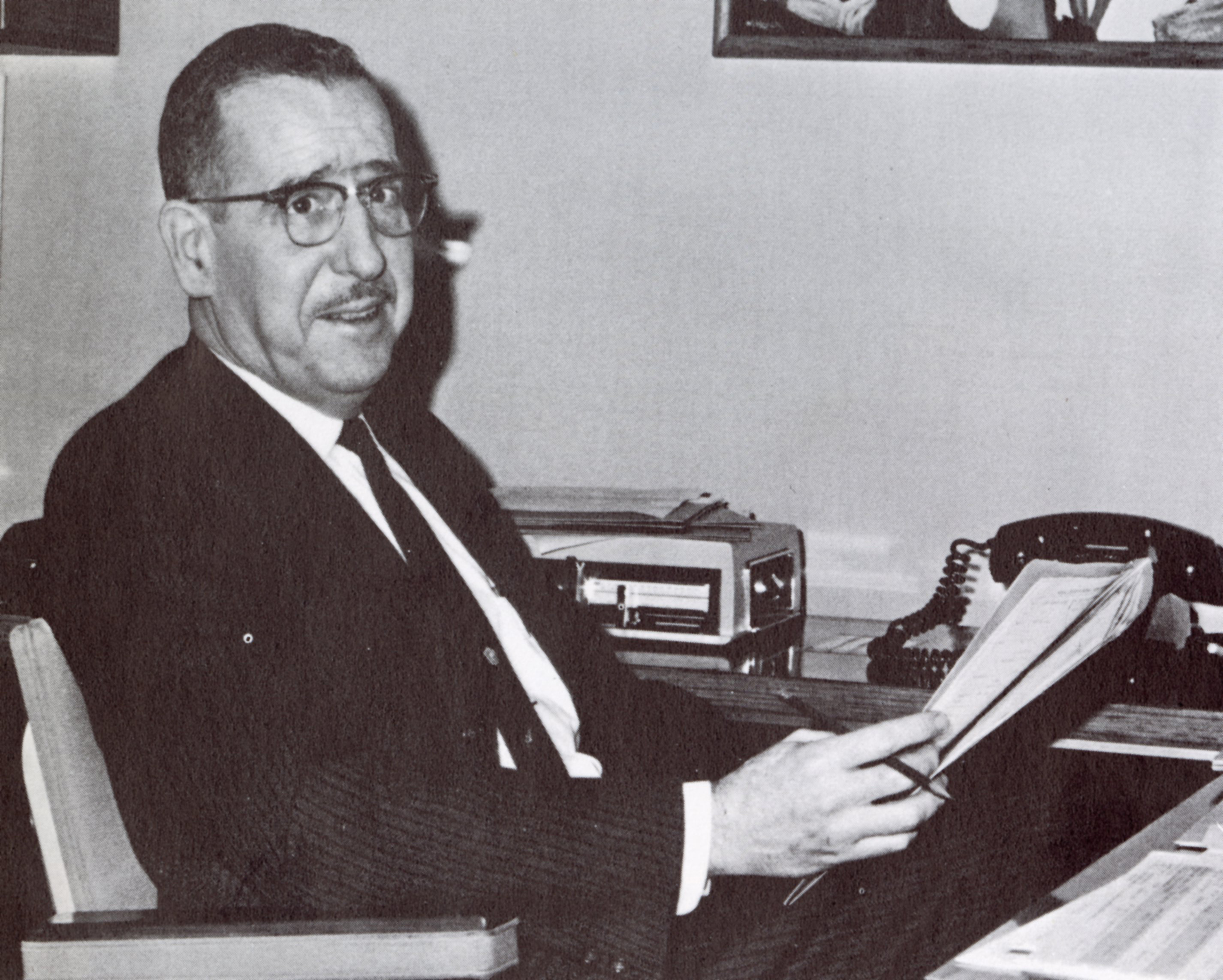

Former admissions dean Miles Hench, Ph.D.

Medical school dropout. A second-time applicant. Former math teacher. Underperforming undergraduate.

Aspiring physicians worried those labels would keep them out of medical school. Instead they would go on to credit Hench with giving them the chance to live out their dream of practicing medicine.

"It is not hyperbole to say that he changed my life," says radiologist Michael Komarow, M'71. Nervous about a less than stellar undergraduate grade point average, he remembers Hench immediately put him at ease during his admissions interview.

He recalls that medical school interviews could start to feel a little repetitive — schools ask the same questions, prospective students give the same answers. But an interview with Hench didn't follow the standard blueprint.

He set the tone by coming out from behind his desk to interview applicants, sitting next to them at a table in his office. The small, yet meaningful, gesture had such an impact on Tom Scalea, M'78, that when he went into practice, he immediately bought a table and two chairs. "I never talk to anybody from behind a desk."

Hench also had a way of showing he wanted to get to know the person behind the grades and test scores.

"I felt like he came in with a positive attitude to get to know me and see where I could fit into the class structure," says ophthalmologist Sara Jones-Gomberg, M'80. "He hadn't counted me out yet."

The effort made an impression on Jones-Gomberg, who arrived on the MCV Campus at age 28 after earning a graduate degree in mathematics and spending a few years as a teacher. Given her late entry into medicine, she says, "I was probably a bit of a gamble on his part. Every day I'm so thankful that I was given this experience."

Larry Schlesinger, M'71, knew he was a gamble. He applied to the Medical College of Virginia after failing out of University of Michigan Medical School. While nearly three years in the U.S. Army helped him mature after Michigan, the time didn't diminish the calling he felt to a career in medicine. Soon, he found himself on the admissions interview trail for a second time.

It was a bumpy road. Another medical school dean told him, "You are a proven failure. You will never get into medical school." His top choice, MCV, placed him on the waiting list.

The 1967 school year began and with no word out of Richmond, Virginia, Schlesinger started medical school at Michigan State University. Then, a letter arrived from Hench.

"Congratulations! You have been chosen for the Class of 1971."

The last one admitted, he started his classes 13 days into the first semester. Today, he is a successful plastic surgeon living in Hawaii, where he has earned Physician of the Year state honors.

"I have no doubt how I got where I am today," he says. "It all had to do with MCV and a dean of admissions who had enough guts to let in a proven failure. Without MCV and Dr. Hench, I would be nowhere."

To show his appreciation for the institution and man who graced him with a second chance, Schlesinger gave a generous gift to create the Dr. Miles Hench Scholarship housed at the MCV Foundation [see companion story].

A student advocate

Some called it the "Hench hunch." Or a sixth sense. Others may have even thought Hench's instincts were flat wrong.

"He would fight for students," Valentine recalls of her father. "He didn't always win. But he would fight. It was difficult for him that he couldn't take more students who were qualified."

While students, both Komarow and Schlesinger served as voting members on the admissions committee, where they witnessed Hench put together a medical school class firsthand.

"As Dr. Hench saw it," Komarow says, "his job was to find those most likely to become good doctors — to pick the ones who would get the most from MCV and return the most to medicine and their patients. Was the applicant a person who could be empathetic, mature, not hideously competitive, not bigoted and self-motivated? A host of factors all contributed to committee discussions and to ultimate determinations."

According to Valentine, her father often said if you can't relate to people, you can't be a good physician.

"Anybody can learn. Not everybody can relate. That's the thing I remember most."

Jones-Gomberg says Hench continued to look out for students throughout their four years of medical school. He played a part in advocating for one of her classmates to graduate a year early because she had a baby and her husband accepted a residency out-of-state; similarly, a struggling student dropped back a year to graduate with Jones-Gomberg's class.

Throughout his career, Hench humbly credited the students for their medical school successes, not his decision to admit them. He told Schlesinger, "You deserved a second chance." The rest, he added, was up to him.

"One of the greatest joys in his life was to see those students be successful," Valentine says.