Piece of the Past

The 1963 death of President John F. Kennedy's son at 34 weeks gestation spurred the creation of the neonatology field. In 2023, the NICU celebrated 50 years of saving the littlest lives on the MCV Campus.

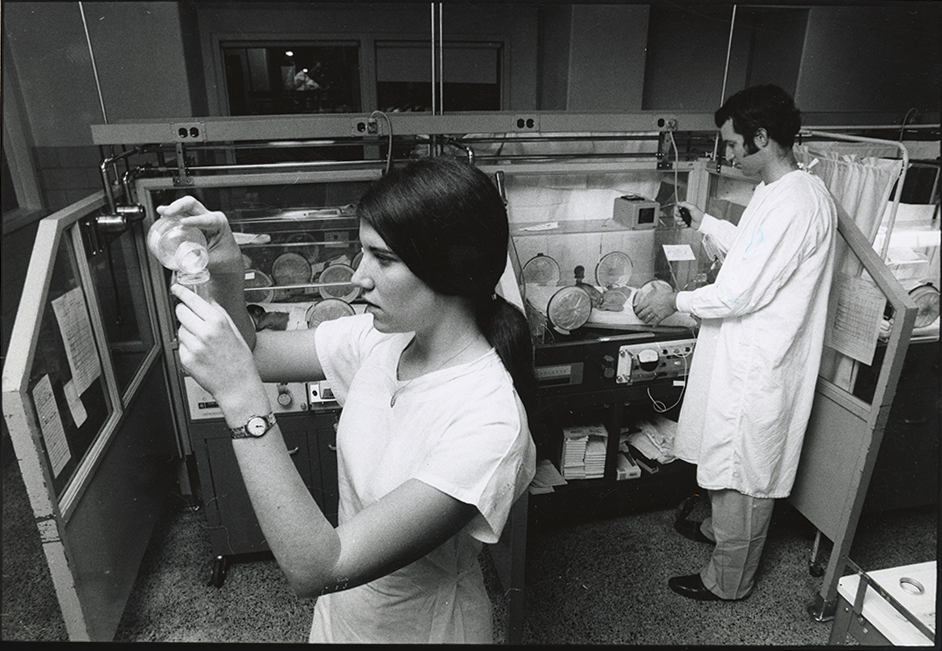

Courtesy of VCU Special Collections and Archives

This story was published in the spring 2024 issue of 12th & Marshall. You can find the current and past issues online.

The standard of care for treating critically ill or premature babies prior to the 1960s was quite simple. It didn’t exist.

Until the advent of neonatal intensive care units in the ’60s and ’70s, the prevailing wisdom was that these babies wouldn’t survive, or if they did, they wouldn’t thrive.

“At the time, pediatricians were hands-off when it came to premature babies,” says BARRY V. KIRKPATRICK, M’66, H’71. “They didn’t believe in interventional care. They thought these babies had a good chance of dying.”

This mindset dramatically changed with the 1963 death of President John F. Kennedy’s son at 34 weeks gestation. The event spurred the creation of the neonatology field and the push for technologies to treat what was then known as hyaline membrane diseases, a condition that killed about 25,000 children a year.

In 1973, Kirkpatrick established Central Virginia’s first NICU at MCV Hospitals. By 1982, it was treating 900 patients a year and transporting more than 300 patients from outside facilities as the referral unit for 13 regional hospitals. By 1986, it was one of the largest units on the East Coast.

In 2023, the NICU celebrated 50 years of saving the littlest lives on the MCV Campus.

As founding director Kirkpatrick remembers the pace and urgency of those early days when he was the lone neonatologist on the unit.

“I was on call every day and every night for two years straight,” he says. “When that changed to call every other night, I thought I had died and gone to heaven.”

He oversaw a series of milestones — including first on the East Coast to use an ECMO machine — and developed the staff not only at the medical center but also in the community, traveling with “a cadre of nurses” to teach other hospitals and paramedics how to resuscitate a sick baby.

Their commitment to the emerging specialty paid off. Within three to four years of the NICU’s creation, the pediatric community was on board after seeing high-risk infants including premature babies grow into healthy, thriving toddlers.

Now, 50 years later, the NICU has evolved beyond what rotating medical students, residents and fellows may remember as cutting edge in the 1970s and 1980s. For example, the large, noisy bays housing dozens of premature or critically ill babies have been replaced with quiet, single rooms that destress infants and discourage maternal separation.

“Operative suites are embedded in the NICU to avoid the movement of children that is known to disadvantage their outcome,” says KAREN HENDRICKS-MUÑOZ, M.D., M.P.H., professor and the William Tate Graham, M.D., endowed chair in the Division of Neonatal Medicine and deputy director of the VCU Center on Health Disparities.

She notes that two-thirds of today’s NICU admissions are focused on critically ill term infants with congenital conditions that impact their heart, lung, intestine or brain function. Numerous developed clinical programs are now not only standard of care but areas of excellence, helping contribute to a top 50 neonatology program ranking from U.S. News and World Report in 2023-24.

These include advances in modes of respiratory care such as high frequency ventilation, ECMO and surfactant therapy to dedicated NICU psychologists or the arctic hypothermia cooling programs for the treatment of infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Nutrition and neurodevelopmental therapies begin in the NICU and continue in the regional neonatal continuing care outpatient follow-up program that just celebrated its 10th year.

New in recent years is a small baby program to optimize the management of infants born at 22 to 25 weeks gestation.

The question of whether the lives of critically ill or premature babies are worth saving has come a long way in five decades. “It’s really gratifying to see the improvement of care for the majority of premature babies,” says Kirkpatrick, who trained 940 pediatric residents along with fellows and hundreds of medical students. In them he instilled the belief that sick babies were still people to be cared for — a perspective they then carried with them into their careers.

There’s more to be done every day. Hendricks-Muñoz’s vision centers on continuing to contribute to medical care advancements and educating and inspiring the next generation “to continue to push the envelope in our understanding and technologies so that every newborn can have a healthy life to fulfill their optimal potential.”