A man to fix your achy breaky heart

One alumnus’ country music career in the 1990s is earning newfound, overdue attention

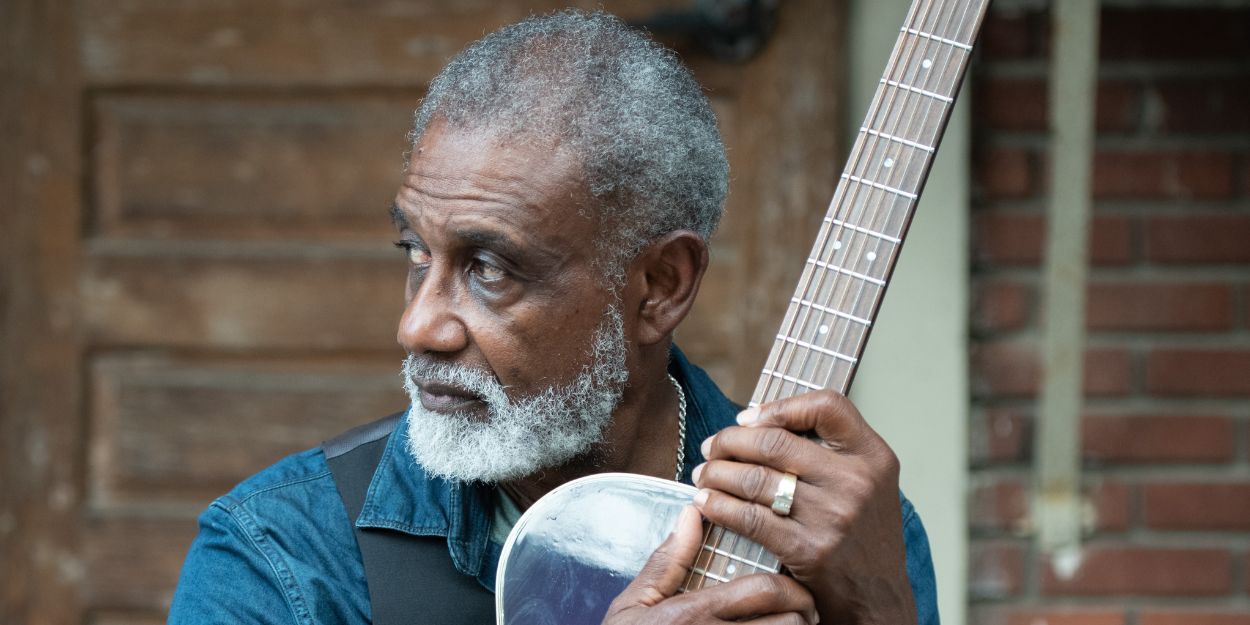

Photo by Rena Schild

This story was published in the spring 2023 issue of 12th & Marshall. You can find the current and past issues online.

Cleve Francis, M'73, was 15 years into a successful medical career when a record label executive gave him a choice.

“He walked in and said, ‘Who in the hell are you?’ I said, ‘I'm a cardiologist.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s your problem. I'd like to sign you to Capitol Records.’”

The executive had seen a music video called ‘Love Light’ that Francis had funded and personally delivered to Country Music Television. He flew Francis to Nashville for the offer of a lifetime.

“I was single at the time, and I probably needed a break from the challenges of cardiology,” Francis says. “I decided to take a sabbatical and see.”

For three years in the early 1990s, Francis recorded albums, starred in music videos, appeared in national media, toured the world and played for audiences in the thousands. Then, having taken his musical career as far as he could, Francis returned to his “first love” of cardiology, a love nurtured on the MCV Campus. But music never went away.

It was part of the culture, he says, growing up in southwest Louisiana, surrounded by the gospel and blues of the 1950s. Young Francis fashioned a guitar from a cigar box, and his mother, impressed with his ingenuity, saved up to buy her 9-year-old son a real one.

Becoming a doctor, on the other hand, wasn’t a natural progression. Francis didn’t meet a Black doctor until he went to college at Southern University in Baton Rouge – the first in his family to receive formal education.

“When I was a kid, in any emergency, you had to drive to a charity hospital about 44 miles away,” Francis says. “Some people made it; some didn't.”

Meeting a Black doctor changed the course of his life. “I switched to pre-med that day.”

But medical schools weren’t accepting applicants from his historically Black university, and Francis ended up at the College of William & Mary, working with reptiles and earning a master’s in biology.

From there, along with Archer Baskerville, M’73, Francis was one of two Black students admitted to the freshman class in 1969.

“I loved Richmond,” Francis says. “It was a capital of the Confederacy, but MCV was pretty well isolated. We were just studying. Everybody was in the same boat. Archer and I, we blended in. We became part of it.”

At medical school, he and some of his classmates arranged jam sessions in the lobby of the nursing dormitory on Friday nights.

“I was singing more folk then – ‘soulfolk,’” says Francis, who was later elected vice president of his class. “The music drew us all together. I think a lot of guys met their wives in that lobby.”

During breaks from school, Francis returned to the Tidewater area to perform with local folk groups. Loans and scholarships helped Francis get through medical school, but the money from concert gigs allowed him to buy books, clothes and food.

At first interested in OB-GYN or psychiatry, Francis veered toward cardiology after witnessing a code blue in North Hospital, where cardiologists calmed the room and stabilized the patient.

“‘That's what I want to do,’” Francis says he thought. “I want to organize chaos when it’s life and death.”

A residency in internal medicine and a cardiology fellowship at the George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C., followed. Then Francis started Mount Vernon Cardiology Associates, which later became the second largest cardiology practice in Northern Virginia. And that’s where he was when the music executive heard his honey smooth vocals and saw his face on CMT.

“The biggest person I had to convince, when I was deciding to take the record deal, was my mother,” Francis says. She grew up in segregation and poverty, he adds, but all six of her kids became professionals.

“My mother was quite proud of that feat, and she wanted to be sure that I was making the right decision – to follow my heart, but not lose what I’d struggled for.”

Francis traveled the world, singing hits like "You Do My Heart Good," "Walkin,'" and "We Fell in Love Anyway.” He recorded music videos that got heavy rotation on CMT.

“I played Fan Fair in Nashville in front of 25,000 people,” he says. “I played June Jam in Alabama in front of 75,000 people. I’ve been on every national television network, all the major newspapers. I think overall people accepted my gifts kindly.”

Francis’ mother got to see it all. And she saw his successful return to cardiology after three years. Francis figured he’d gone about as far as he could in the music industry.

“I was older, and I was a Black artist in country music,” he says. “Plus, I was a cardiologist and I had a lot of people to serve.”

Francis worked for another 25 years, selling his practice to Inova Health System and retiring from clinical work in 2021. Now he’s a diversity adviser for the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, and he writes and lectures on patient personalization, bias and racism in health care. In 2018, he received the Pioneer Award from the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute for lifetime achievements in cardiology.

He’s continued to play and perform. And his work is being rediscovered by a new audience. Francis’ earliest recordings from the 1960s were re-released last year as “Beyond The Willow Tree.” And a Washington Post profile last July considered how far Francis might have gone if not for racial bias in the country music industry.

Francis laid the groundwork for other Black artists. He founded the Black Country Music Association to support others in the genre. And these last few years have brought awards belatedly recognizing his contributions to country music, including the 2022 Black Opry Icon Award. His music is included in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“I got a chance to live two lives in one person,” Francis says. “How many people actually have that chance?

“I'm probably the only cardiologist in the world who had this experience.”