An internal medicine resident was trying to give a brief presentation on different types of IV fluids to an audience of two interns and a medical student.

Things were not going well.

One of the interns was clearly interested, but the other appeared distracted, and impatiently interrupted the resident. Could he cut to the chase? Could he just tell them the key points they needed to know? Meanwhile, however, the medical student seemed lost and unable to follow the presentation. What was that term you used? Could you repeat that? Can you explain that?

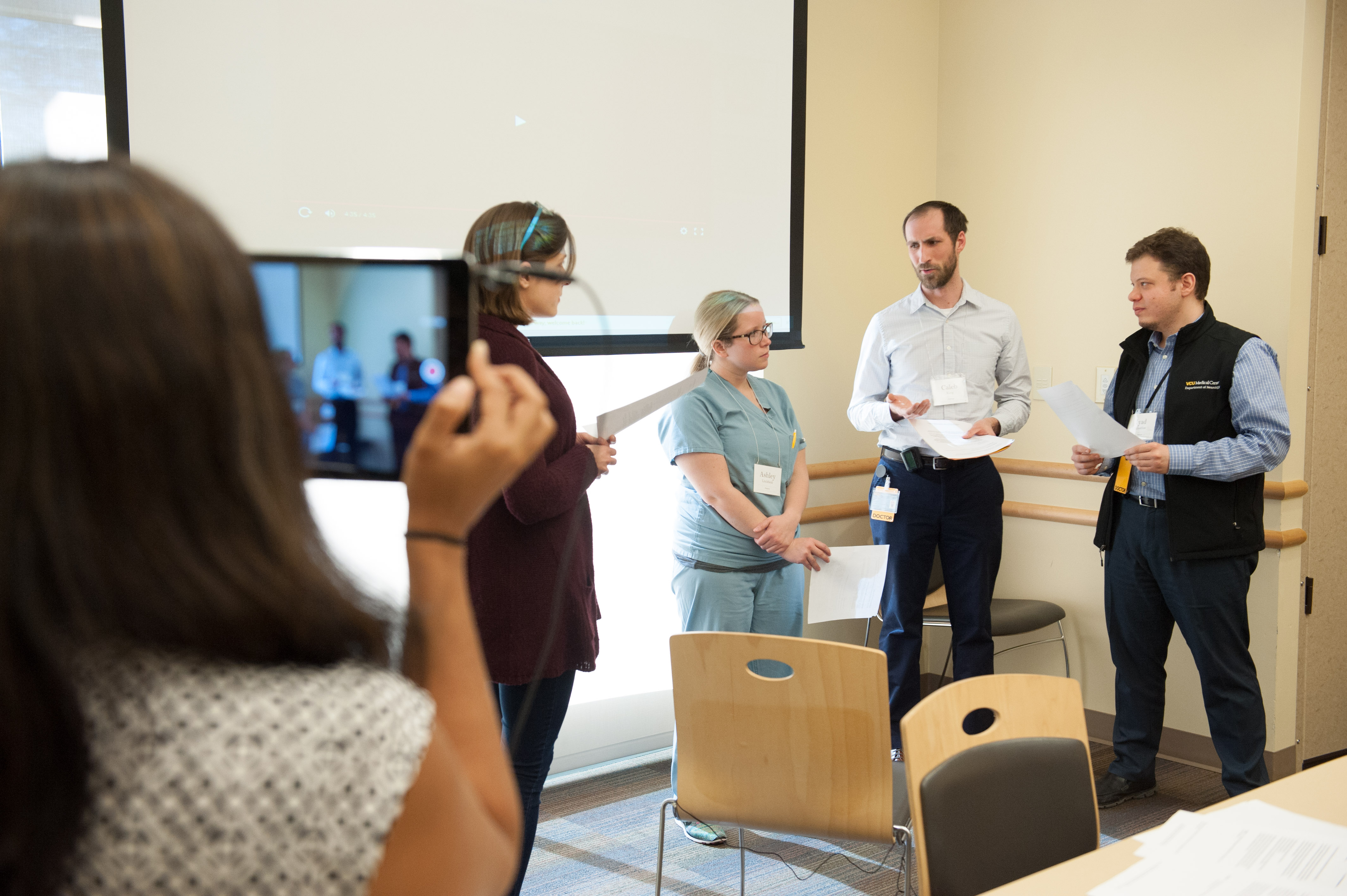

Finally, Reena Hemrajani, H’10, stepped in. Associate program director for the internal medicine residency, on this day she was taking the role of facilitator in a two-day workshop on the art of effective teaching. The workshop participants were all second-year internal medicine residents, and the scenario that had just unfolded was a scripted role-play. The interaction was specifically designed to present the kinds of challenges and frustrations residents are likely to encounter in an actual teaching situation.

“How did it feel to be in the role of teacher?” asked Hemrajani.

“I think,” reflected the resident, “that we often overshoot the knowledge base of our students.”

Hemrajani, who is an assistant professor in internal medicine, confirmed his idea. “The hardest part of teaching is remembering what they don’t know.”

During the workshop, roleplaying scenarios are videotaped so residents can analyze the challenges and frustrations that occur in actual teaching situation. They also get a chance to try simple behaviors for creating a more effective learning climate, giving feedback and organizing their teaching.

LEARNER AS TEACHER

By the time you graduate from medical school, you’ve spent years – almost your entire life – as a learner. Then you start your residency, and even though you’re called “doctor” now, you’re still fully aware of how much you have yet to learn. Suddenly you find yourself stepping into another new role you hadn’t really anticipated, a truly unfamiliar one that you might never even have thought about until the first day you’re expected to take it on.

Suddenly, you’re a teacher.

You’re a teacher, and that medical student who only a year ago was you is now looking at you for guidance. And you’re expected to know what to do.

“It is a huge mental shift, and when you think about being a physician, you really don’t think about the teaching part of it,” says Morgan Vargo, PGY2, who was taking part in the workshop. “Not only are you teaching in residency or if you become an academic practitioner, but you are always going to be teaching your patients too.”

In the Graduate Medical Education program on the MCV Campus, helping accomplished learners begin the journey to becoming effective teachers is the focus of the workshop in teaching skills. For a decade, it’s been offered annually to all second-year residents in internal medicine and, more recently, has been expanded to reach residents across the specialties.

The seminar is based on a framework developed by a Stanford internist. It focuses on seven categories — like feedback, communicating goals and promoting understanding and retention — that, though not necessarily intuitive, are essential for effective teaching.

“Most of student and intern education is from the senior residents when the attendings are not in the room, so teaching residents how to teach effectively is critical,” says Stephanie Call, M.D., who is the residency program director and associate chair for education in VCU’s Department of Internal Medicine.

Call has been facilitating the Stanford framework for more than a decade. The workshop offers an introduction to “really simple behaviors residents can use,” says Call, “particularly for creating a more effective learning climate, giving feedback and organizing their teaching.”

Beyond the skills it cultivates, the workshop also serves to reinforce to busy residents the School of Medicine’s commitment to creating not just great physicians, but also great teachers.

Gregory Trimble, M’03, another facilitator, is assistant dean for faculty at the VCU School of Medicine’s INOVA Campus in Fairfax. He notes that his own passion for teaching was discovered during residency and says that he emphasizes the important role residents play in medical education. “I remember coming out of medical school I felt well prepared entering residency,” he says, “and the people who were most influential as teachers were the house staff.”

John Greer, MD-PhD’13, is a third-year neurosurgery resident who completed the workshop earlier in the year. He says, “It was a good reminder that we are really positioned as residents to be teachers. Even when we are really busy and tired and there are lots of things we are still learning, we have to take the time and make the priority to teach the medical students and junior residents.”

Gregory Trimble, M’03 (center), is assistant dean for faculty at the VCU School of Medicine’s Inova Campus in Fairfax. He says he discovered a passion for teaching during residency. “I remember coming out of medical school I felt well prepared entering residency,” he says, “and the people who were most influential as teachers were the house staff.”

FACILITATING LEARNING

Central to the resident-teaching workshop are the role-playing scenarios. They’re video-taped and analyzed in small-group sessions, giving the residents opportunities to try on different teaching situations, to see themselves in action, to think about what they might or might not do differently. As one resident contended with his restive audience of residents and medical student in one room, in another, Derek Leiner, PGY2, played the role of the impatient intern, checking his pager, taking a call on his phone.

Improvising, the resident taking the part of the teacher commandeered Leiner’s attention by engaging him and asking a question related to one of Leiner’s own patients. In the discussion that followed, Leiner acknowledged it was an effective tactic. “It was hard to pretend I had more important things to do when we were talking about my own patient,” he said.

Throughout the role-play, session facilitator Call was quick with warm praise: “Great job.” She posed thoughtprovoking questions: “How do you feel about giving reading assignments?” She offered helpful suggestions: “Develop little canned talks on something you are comfortable with, that you’re likely to have on your service.” She acknowledged challenges and limitations she’d faced in her own efforts to become a better teacher, like having to learn not to talk in a monotone when she was nervous.

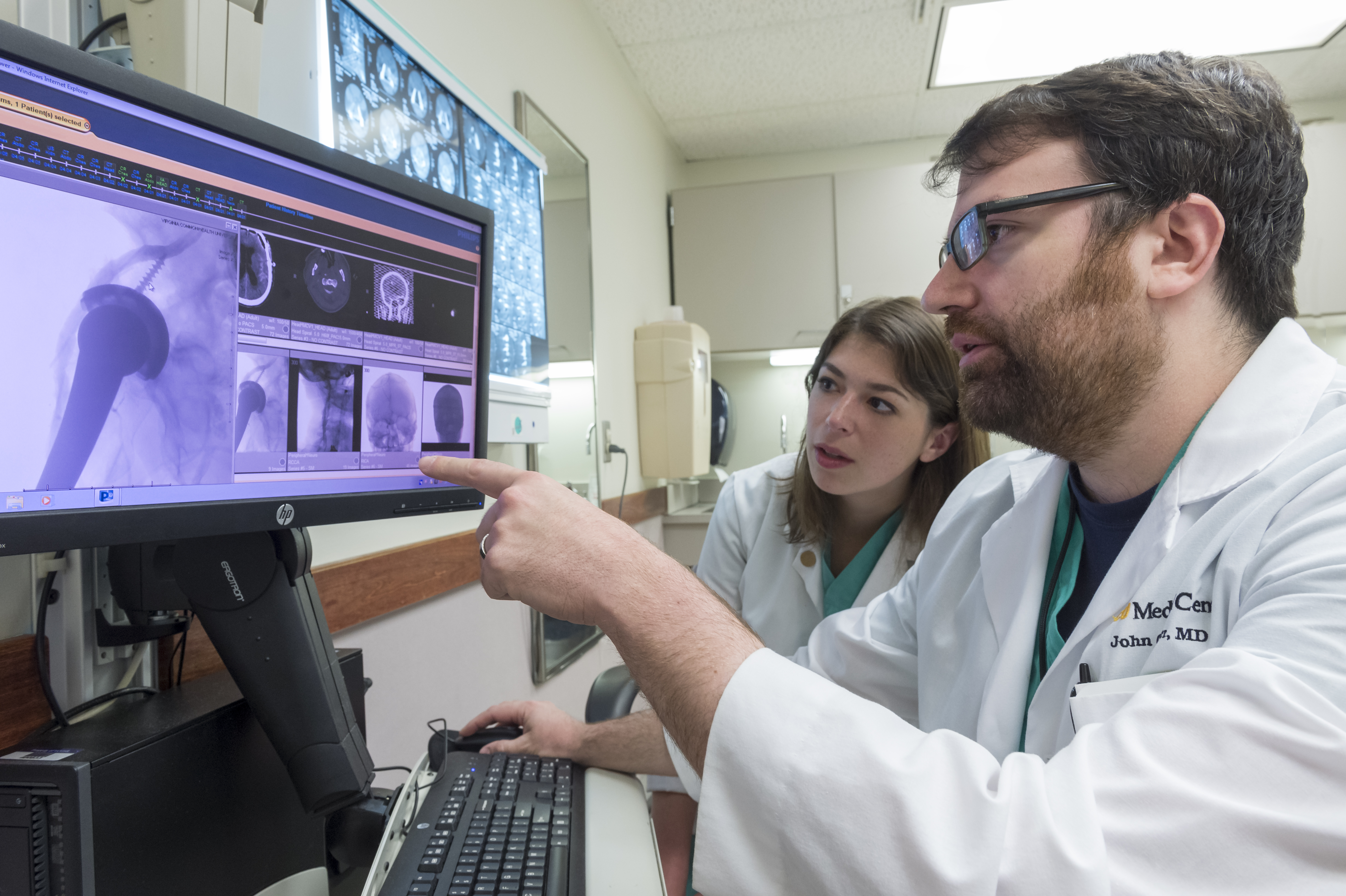

Third-year neurosurgery resident John Greer, MD-PhD’13, makes a point of tailoring his teaching

to medical students’ career interests. That’s what he did with the Class of 2017’s Emily Kershner who’s considering emergency medicine as a career, but spent two weeks with Greer as part of her surgery rotation.

Animated, lively, enthusiastic, engaging, genuine — Call’s manner seemed anything but forced or scripted. Yet after the session, she pointed out that a great deal of thought and planning, refining and improving goes into every detail of how she and the other facilitators lead the workshop, that everything they do actively models and reinforces the very teaching strategies being learned. The residents, she says, “could label every behavior I used.”

Admitting her own limitations? The residents would call that creating a comfortable “learning environment.” Asking questions that lead to self-reflection? “Promotion of understanding and retention.” Even keeping the sessions on time — the role-play breakouts wrapped up right at 10:30 a.m., as the printed workshop schedule indicated — is part of the framework, under “control of session.”

“We think about everything, every aspect,” says Call, noting that every time she facilitates a workshop, she learns more herself.

“If we feel like the teaching is not going well, we adjust and ask ourselves, what are the behaviors I could use to make this go better?” adds Hemrajani — which is exactly what they want residents to learn to do as well.

SETTING THE STAGE

A few weeks later, second-year resident Leiner, looking back on the seminar, says he found the experience eyeopening. He’d gone into the workshop thinking he knew about teaching: his mother-in-law is a teacher, he has friends who are teachers, and of course, “I had been in school and seen plenty of teaching,” he says.

“But all the behind-the-scenes aspects of teaching I had never considered before, how there is so much more to teaching beyond the passage of knowledge. The learning climate, how you present yourself, how these factors relate to what you are trying to teach — I had not realized all these things are in play.”

Leiner says he took away strategies that he believes will be “very, very effective” in changing the way he will approach learners. “It showed me different techniques to use but also showed me that just the way I ask a question could change the way I pass on knowledge.”

Neurosurgery resident Greer says that he also found the experience immediately valuable. He notes, for example, that he now has medical students set goals at the beginning of a rotation and then provides them feedback on those goals at the end.

“Before this class I would never have walked in and said, ‘Hey, you have two weeks, what do you want to learn in that time?’” says Greer. “It was a good reminder about how we approach medical students and how we can give them the best education even though we only have them for a short time.”

Story by Caroline Kettlewell

Photography by VCU University Marketing