From the heart of Downtown Richmond, caring for rural Virginia and beyond

The School of Medicine and our alumni are advancing care, from the local level to the national stage

The Dean's Equity Scholarship helps eliminate barriers to access for students like the Class of 2025's Madalyn Fritch Lee, who grew up in rural Pennsylvania.

This story was published in the spring 2022 issue of 12th & Marshall. You can find the current and past issues online.

Braveen Ragunanthan, M’17, first landed in Mound Bayou, a rural town of fewer than 1,500 people in the Mississippi Delta, in 2009. Ragunanthan was there as a Robertson Scholar, a leadership development program at Duke University, and spent the summer working at a camp for local children.

Ragunanthan returned to Mound Bayou again in summer 2012, shortly before enrolling at the VCU School of Medicine. He couldn’t yet explain the draw, but a seed had been planted.

The seed continued to grow on the MCV Campus, where he participated in the medical school’s four-year International/Inner City/Rural Preceptorship program. I2CRP fosters the knowledge, skills and attitudes physicians need to provide high-quality, compassionate care to underserved populations.

“I2CRP really aligned with my values for why I was going into medicine,” he says. “I was committed to the medically underserved. Medicine has been my vehicle for social justice.”

Braveen Ragunanthan, M'17, says the medical school's I2CRP program solidified his commitment to caring for underserved populations. He and his wife Nina Ragunanthan, M.D., moved to rural Mississippi in August 2021 to begin their post-residency careers.

Ragunanthan also received the National Health Service Corps scholarship, which requires two or more years of service in areas experiencing a shortage of health professionals. He completed clinical rotations in Deltaville — working under Karen Ransone, M’92, H’95 — and Luray, Virginia. His primary care residency track at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh provided two rotations in rural Pennsylvania.

Over time, his experiences coalesced, and he set his sights on becoming a rural pediatric primary care doctor. His wife Nina Ragunanthan, M.D., a graduate of Harvard Medical School, chose to specialize in OB-GYN.

As the couple finished their residencies and wondered where to begin their careers, their minds kept coming back to that that summer in Mound Bayou.

They reached out to its Delta Health Center – the first federally qualified community health center in the U.S. With funding from the Affordable Care Act, the center had experienced a resurgence in recent years, leading to a new building and additional staff.

“It was the right timing when we reached out to see if they needed a pediatrician and an OB-GYN,” Ragunanthan says. “They said yes, and we moved last August.”

How does an urban academic medical center teach the ins and outs of rural medicine?

Ragunanthan is one of many graduates who found the School of Medicine equipped them with the tools to practice in a rural setting. In fact, the school’s Department of Family Medicine and Population Health was founded on that very premise.

The department was established in 1970 by the Virginia governor and General Assembly, charged with educating and preparing family physicians who would then serve the state of Virginia. There also was a particular emphasis on rural areas, which traditionally had trouble accessing and maintaining consistent health care, leading to poor health outcomes.

“Look around the state, and many of the family medicine doctors in rural areas are trained by our medical school and our residency programs,” says Scott M. Strayer, M’94, H’97, chair of the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health. “It remains a significant focus.”

Building that pipeline requires a multifaceted approach, and decreasing student loans are a common starting point. In many cases, students are excited about the prospect of delivering babies, caring for geriatric patients and everything in between. But when faced with hefty student loans, some say they turn to specializations with higher salaries.

The School of Medicine’s Family Medicine Scholars Training and Admission Track (fmSTAT) program offers financial relief in the form of privately funded scholarships, as well as supplementary seminars and extra clinical and volunteer opportunities that can be tailored to an interest in rural medicine.

Meanwhile, the Dean’s Equity Scholarship helps eliminate barriers to access for students of all backgrounds, cultures and socioeconomic status, religion or geography — including those from rural areas, such as the Class of 2025’s Madalyn Fritch Lee.

Growing up in rural Pennsylvania, Lee was primarily familiar with family medicine doctors from her experiences as both a patient and shadowing several physicians. She liked the idea of caring for multiple generations of families and seeing a patient from birth to end of life. But she also saw how some patients struggled to access quality health insurance and avoided costly and inconvenient doctor’s visits.

Those experiences will benefit her future patients — she is interested in family medicine and outreach to underserved areas through rural and wilderness medicine. They also benefit her classmates who’ve been learning from the stories she shares of the challenges she witnessed.

Strayer says opportunities for mentorship and exposure are vital to helping students pair the school’s urban, academic medical center training with the experience of practicing in a rural area. Placing community members in rural towns doesn’t just give them hands-on training with the rural doctors who may serve as guides throughout their careers. Being embedded in the community also helps the future physicians connect with community members and appreciate life in a small town. In many cases, residents end up staying long-term.

“It’s hard to tell someone from across the country, ‘Come to this great place,’ unless they’ve experienced it,” Strayer says.

Rural physicians have to know ‘more than medicine’

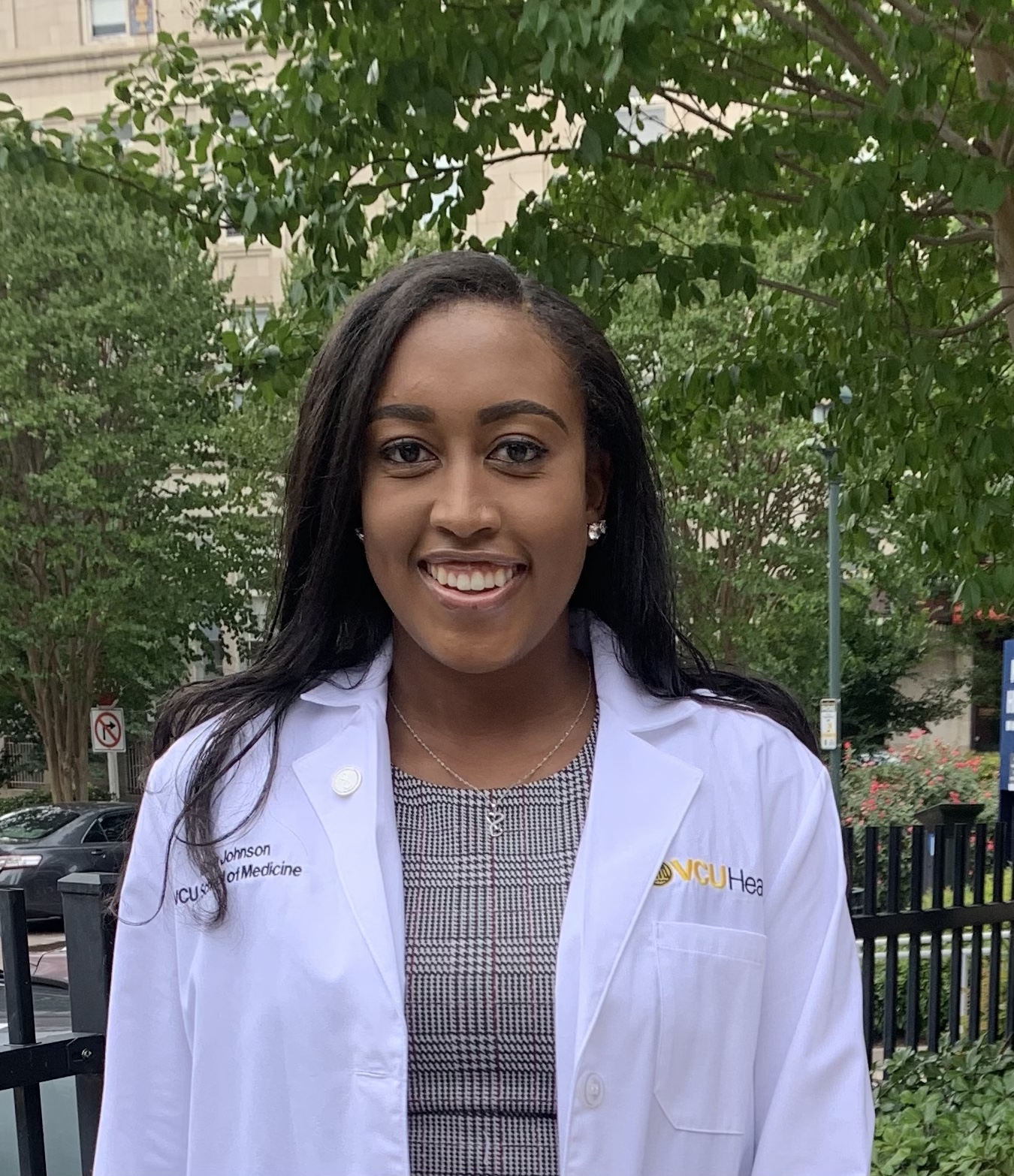

I2CRP student Maya Johnson

As an undergraduate, Maya Johnson was first introduced to the idea that social, geographic and environmental factors can determine a patient’s access to health care. Once she realized the gaps existed, she knew she wanted to focus on underserved communities.

Johnson found that opportunity at the VCU School of Medicine and, in particular, the I2CRP program. The third-year medical student says the topical lectures and speakers have given her a better understanding of social determinants of health and opened her eyes to new specializations. In addition, preceptorships and clerkships have given her a firsthand look at the realities of practicing medicine in underserved settings — both rural and urban.

Her two clerkships in Blackstone, Virginia, and on the Eastern Shore revealed that no two rural practices are the same. For instance, she saw how doctors on the Eastern Shore had to be deeply familiar with workers’ compensation regulations in order to support their patients who worked for poultry processing plants and other nearby factories.

“The doctors had to be well-versed in what factory work was like and how it contributes to their patient’s health,” Johnson says. “I saw how much they knew about things other than medicine in order to take care of their patients.”

‘We take care of an entire community’

Since returning to Mound Bayou, Ragunanthan says he’s enjoyed reconnecting with the patients and families he met more than a decade ago. But the work has also been challenging. Mississippi has one of the nation’s highest rates of childhood poverty, childhood obesity and infant mortality, and the Delta region is exceptionally disadvantaged. Founded by former slaves after the Civil War, Mound Bayou is one of the country’s oldest historically Black communities and served as an oasis from many other towns in the Delta that endured years of racial oppression.

Rural representation

Increasing access to care and rural representation among physicians are only parts of the puzzle to better understanding health care needs across the country. Rural residents are also historically underrepresented in clinical research.

That’s why the VCU C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research announced a new funding program aimed at helping researchers recruit study participants in rural areas. The Rural Pilots Voucher Program offers VCU researchers and investigators up to $25,000 for telehealth technology, advertisements and more to engage hard-to-reach patient populations.

Ragunanthan’s wife is the only OB-GYN at the Delta Health Center where they both work, and Ragunanthan is one of only a handful of pediatricians in the area. He says the ER calls with questions, and he regularly attends deliveries with OB-GYNs from area private practices.

“In a city, I had everything at my fingertips,” he says. “I wasn’t ‘on’ all the time. But here, part of being a pediatrician in a rural community, I have to be a jack-of-all-trades.”

As a third-generation family physician, Sterling N. Ransone Jr., M’92, H’95, was prepared for some of those challenges when he started his own rural practice in Deltaville, Virginia. But he didn’t expect that an insurance company would decline a prescription simply because he was a family doctor.

“The insurance company insisted that I have my patient take another day off from work and drive a half-hour to go to a specialist,” he says, “who looked at my workup and wrote the prescription in less than three minutes.”

Ransone responded by writing to the insurance company, with no response. Then, he put a resolution in front of the Medical Society of Virginia that insurance companies shouldn’t be able to infringe on the prescription authority of a physician. The society adopted the resolution and successfully lobbied the insurance company to revise their policies.

After collaborating with other physicians to influence change, Ransone was hooked. He joined the board of the Virginia Academy of Family Physicians, followed by the Medical Society of Virginia. He was recently named president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, which represents 133,500 physicians and medical students across the country.

In each of these positions, Ransone has advocated for changes to the U.S. health care system that empower family physicians to take better care of their patients. Over the years, those have ranged from removing administrative and regulatory roadblocks, to securing the medical malpractice cap, to testifying before the U.S. Senate about the need for increased broadband access. Most recently, he’s focused on ensuring telemedicine resources after seeing its use by family physicians grow from about 10% to 90% during the pandemic.

Another priority is recruiting more young physicians to follow in his footsteps. The AAFP predicts a shortage of more than 52,000 primary care physicians by 2025. In response, the organization has set a goal to have 25% of U.S. medical students specialize in family medicine by 2030.

“If you've never been to a rural area, it's hard to know what you’re getting into,” Ransone says. “If you've never been away from the hospital setting, it's daunting to go out and not have those services right there at your beck and call. We need to show medical students exactly what we do and how we can take care of an entire community.”

Learn more about how the medical school, its residency programs and its alumni are increasing access to care in rural areas.