Looking onto I-95 and into brain injury

When John Povlishock, Ph.D., came to the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology in 1973, he could almost see his calling from his office window: Interstate 95, with a reputation for speed – and unfortunately, horrific crashes. Those resulting injuries – especially neurotrauma – were claiming way too many lives.

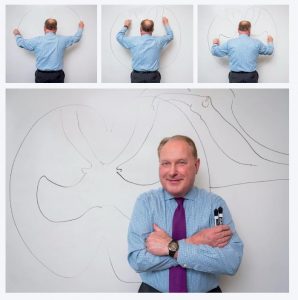

A showstopper: many alumni remember John Povlishock, Ph.D., and his ability to draw with both hands simultaneously. This ambidextrousness, he says, comes from being able to turn off the conscious mind. “You cannot really think through the motions or it all breaks down. You’ve got to let your body take over.” Photography by Allen Jones, VCU University Marketing

But from his MCV Campus vantage point on the I-95 corridor, Povlishock and colleagues found a way to help. Not only did their research save lives, they put VCU on the world stage while inspiring generations of other researchers around the globe.

Today, Povlishock leads a department that in addition to its role in the formal M.D. curriculum, participates in VCU’s Interdepartmental Neuroscience program for Ph.D. students while also providing research training opportunities for postdoctoral scientists. He’s considered a pioneer in traumatic brain injury research and has developed an international reputation as a scholar and educator. His department’s research groups concentrate on glial cell biology, neuroplasticity, and central nervous system injury and repair.

IDENTIFYING NEEDS, SOLVING PROBLEMS

When Povlishock arrived at VCU, the field was uncharted, the equipment limited and the research needs high.

“There was no protocol for management of traumatic brain injuries, which today sounds

unbelievable,” Povlishock recalls. “Many people who were seriously injured in automobile accidents came in and the chance of dying … the mortality rate was about 73 percent.”

Former neurosurgery chair Donald Becker, M.D., was frustrated, Povlishock says, trying to understand what was going on with the injured brain, so he began to form a dream team of researchers to investigate. “We were focused on severe traumatic brain injury, and we thought traumatic brain injury was a singular disease,” Povlishock says. “That sounds naïve today, but we thought it was one-size-fits-all.”

Povlishock, with expertise in the blood-brain barrier, was pulled onto Becker’s team. The VCU team grew, “and we created this perfect environment, employing a very scholarly and translational approach. It really was a wonderful time.

“It was like the Camelot of neurotrauma research.”

What Povlishock and colleagues generated during that Camelot era was revolutionary and established them as pioneers in the field. But, of course, that research required funding, so Povlishock approached the National Institutes of Health, which led to a career of interaction with the agency.

“At first, there was some reluctance, because many were afraid we were going to take those 73 percent of people who were dead or dying and move them to a vegetative state,” he recalls. But ultimately VCU received NIH funding, and went on to complete groundbreaking work that has helped reduce the neurotrauma mortality rate to about 30 percent, while also improving other outcomes.

“Part of that was increased recognition that good medical management impacted these patients,” Povlishock says. “The VCU team focused on admitting the patients rapidly, getting them promptly intubated, and getting them physiologically stable as soon as possible. And that was extremely powerful in improving outcomes.”

What Povlishock did in the research lab translated to better bedside care, says Harold Young, M.D., professor and former chairman of the Department of Neurosurgery. “He has made this a better medical school and a better hospital.”

During this period, Povlishock also recognized that damage to the brain’s axons was a delayed reaction to the traumatic brain injury and a major contributor to the patient’s morbidity. “It was not an immediate event and thus, there was a therapeutic window that we could get at,” he explains. For his research contributions, he was awarded two Javits Neuroscience Investigator Awards from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which also awarded him its Gold Medal for Brain Injury Research.

One of the most important findings of the VCU team was to understand the problem of intracranial pressure in brain-injured patients – and to develop targeted treatment protocols. To this day, he says, “it remains a very important and controversial issue. We know that intracranial pressure management saves peoples’ lives. The question we don’t understand is: does it alone improve their outcome in terms of their return to their families and workplaces?”

SHARING LESSONS

With new data, and because there was so little knowledge regarding the brain’s response to injury, Povlishock and colleagues published a definitive two-volume series that became standard reading for neurotrauma research at both the bedside and the

laboratory bench.

VCU’s current chair of neurosurgery Alex Valadka, M.D., H’93, trained as a post-doc scholar with Povlishock a quarter century ago during his residency, and admits to being a little in awe. “He was a pioneer in the field. He’s been at the top of his game for a long time. To this day, when you read journal articles, manuscripts or book chapters, his

name keeps coming up. It’s not just classic works. He continues to lead modern research as well.

“He stands out, because while he’s not a clinician, he’s very well-known in the clinical world, especially among the hard-core neurotrauma and vascular researchers and the neurosurgeons involved with NIH. That’s rare as we get more compartmentalized,” Valadka says.

Povlishock acknowledges his work helped define the field, even as that field has evolved. Treatment options were refined and auto accidents began to decline, thanks to increased use of passive restraints, air bags and increased awareness of drunk driving. Unfortunately, he notes, accident rates have crept up in the past few years, perhaps because of distracted driving. Today he continues his work as principal investigator for research on how mild traumatic brain injury alters axonal structure, neuronal electrophysiology, vascular function and brain circuit reorganization.

With important science has come important recognition. Povlishock’s work has been reported in more than 250 papers, reviews, books and chapters and, to date, his work has been cited over 21,000 times. He’s been honored locally, nationally and internationally, including with the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Outstanding Scientist Award in 2006.

Povlishock was a big draw for the university, says Young, who holds the James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin Endowed Chair. “Everybody wanted to come here, study here and work with him. I used to sit in on his lectures. When he gets on the podium,

everybody listens.”

He could have continued his career anywhere – and had attractive offers – but supportive colleagues, improved equipment and recognition from VCU were good reasons to stay at the university, he says. During his tenure he has been honored repeatedly for teaching as well as with the University Award of Excellence.

Former and current students are glad he stayed. Mary D. Ellison, PhD’85 (ANAT), chief external relations officer at United Network for Organ Sharing, credits Povlishock as an inspiration. “Among other things, John has an amazing talent for connecting the dots among various research efforts and for always being ready with the next questions that require investigation. He’s smart, approachable and remembers everything he’s ever read, when it was published and by whom. He seems to thrive on hard work and the relentless pursuit of creating new knowledge.

“It’s been almost 30 years since I left his lab, and even though I’m now an administrator, not a scientist, I still remember things he taught me (and all of his students) about interpreting data, drawing appropriate conclusions, identifying next questions and how one goes about getting work funded and published.”

GLOBAL IMPACT

One quirk that many students remember is Povlishock’s ability to draw with both hands simultaneously. This ambidextrousness, he says, comes from being able to turn off the conscious mind. “You cannot really think through the motions or it all breaks down. You’ve got to let your body take over.” The trick he learned from a professor during his studies at St. Louis University “is a showstopper,” he admits. “It got students’ attention, and alumni remember me for that.”

Alumni remember him for a lot more, too. “He’s a tremendous ambassador for VCU, getting the university’s name out around the world,” Valadka says. Povlishock has, in essence, created a global VCU footprint of scientists who continue his work. In addition to successful grads like Ellison and Valadka who have a high profile from their Richmond bases, Povlishock trained preeminent researchers such as Dalton Dietrich, PhD’79 (ANAT), who leads the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis; Dan Erb, MS’87 (ANAT), PhD’89 (ANAT), founding dean of the School of Health Sciences at High Point University; and David Okonkwo, MD-PhD’00 (ANAT), director of neurotrauma at UPMC Presbyterian. Other students have gone on to become deans in Japan, China and Eastern Europe.

He gets to see some of them, thanks to a rigorous travel schedule for speeches and conferences. China is a frequent destination, he says, sadly, because of the amount of neurotrauma that rapid industrialization has brought.

Despite his research and speaking schedule, he’s found time for professional service and is a chartered member and chair of numerous NIH review panels, a past president of the National Neurotrauma Society and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Neurotrauma since 1991.

By virtue of his tenure, he’s become a historical figure in the field, Povlishock admits. At last year’s National Neurotrauma Society meeting, he was asked to give a founder’s address. But by his own reckoning, “I’m a guide in the journey to study and treat one of the most complex conditions known to man in the most complex of all organs found in the body.”

By Lisa Crutchfield